Guest Post by Geary Sikich (first posted on CERM ® RISK INSIGHTS – reposted here with permission)

Introduction

Recently I wrote an article titled “Can You Calculate the Probability of Uncertainty?” The article posited that the heavy dependence on mathematics to determine the probability of risk realization may actually create “false positives” regarding the basis for the determination of probability.

My point was that there is too much uncertainty, things that we just do not know, to be able to calculate the probability of uncertainty with any degree of confidence. I received several comments from readers telling me that I was confusing the issue and that determining the probability of risk is all about “uncertainty”.

I have to say that this gave me pause to think. And, my conclusion is that risk is all about the probability of identified certainties that carry an uncertain realization.

The Unpredictability of Uncertainty

We are limited with regard to how much data can be gathered and assessed with respect to the development of the probability equation regarding the risk being assessed. In this respect time is a critical factor.

The limitations of time on determining probability affect decision making and decision makers. In a sense, events can move faster than you can determine the probability of their occurrence. This leaves decision makers with a quandary; “How much information is needed to make a decision?”

It is incumbent on us all to recognize and understand that all decision making is flawed. Please note, I did not say wrong. Decision making is flawed simply due to the fact that we cannot ever have all the information needed to make an unflawed decision.

Information changes too fast.

As the authors, Stan Davis and Chris Meyers wrote in their 1999 book, “Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy”; “speed, connectivity, and intangibles–are driving the increasing rate of change in the business marketplace”. Intangibles carry a degree of uncertainty as it is extremely difficult to identify and differentiate what an intangible is and how it affects decision making.

In their 2010 book, “Blur: How to Know What’s True in the Age of Information Overload” by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel point out that the printing press, the telegraph, radio, and television were once just as unsettling and disruptive as today’s Internet, blogs, and Twitter posts.

But the rules have changed. The gatekeepers of information are disappearing. Everyone must become editors assuming the responsibility for testing evidence and checking sources presented in news stories, deciding what’s important to know and whether the material is reliable and complete.

“The real information gap in the 21st century is not who has access to the Internet and who does not. It is the gap between people who have the skills to create knowledge and those who are simply in a process of affirming preconceptions without growing and learning.”

When we are conducting risk, threat, hazard, vulnerability, business impact and any other type of assessment we can apply the techniques that Kovach and Rosenstiel present in their book.

While their focus is on the news media, I have distilled their steps so they can be applied to the assessment of risks, threats, etc.:

- Identify what kind of content one is encountering

- Identify whether the information is complete

- Determine how to assess the sources of the information

- Evaluate and assess the information; determine what is “fact” and what is “inference”

- Determine if you are getting what you need; what alternative analyses can be developed based on the information that is available

- Identify what “filters” are being used to reduce the amount of “Noise” and effect of “Biases”

The Nature of Uncertainty in a Certainty Seeking World

Operating in this non-static risk environment requires an aggressive information gathering and analysis program that facilitates keeping abreast of the ever changing nature of risk.

Additionally, organizations must begin to identify and track what may appear seemingly unrelated risks to determine the effect of risk realization on risks directly related to the organization’s activities (connecting the dots if you will). This presents a challenge for organizations, as identifying what I have referred to as “transparent vulnerabilities” are less likely to be identified due to the fact that the organization may not see them as risks until they are pointed out or emerge due to risk realization.

Identifying and tracking seemingly “unrelated risks” can also be time-consuming and resource intensive. However, not undertaking this effort can result in unanticipated risk realization, potentially leading to chaos.

The risk assessment process

We must ask, “Is the comprehensive risk assessment process merely a paper exercise designed to meet regulatory requirements?” The answer may well be “Yes”. According to a response from Ben Gilad to an article I wrote entitled, “Risk the Nature of Uncertainty“; “The highly touted Enterprise Risk Management model has never delivered true strategic risk assessment, and the failure of the Value-at-Risk financial model in predicting the banking system collapse in 2008 have put “comprehensive” risk assessments” to bed”.

Gilad added, “I should point out that at least in my profession (economist) we differentiate between risk (known probability distribution, as in stock market risk) and uncertainty (no distribution of past outcomes).

I believe organizations should focus on the latter, as it is always more strategic (and therefore more crucial for long term performance and survival). Simulations are a tool and obviously, have many applications to risk (tactical), but the real process should be early-warning (strategic)”.

Jana Vembunarayanan wrote in his blog on September 8, 2013 (https://janav.wordpress.com/)

(https://janav.wordpress.com/author/jvembuna/):

Risk versus uncertainty

For a long time, I was assuming that risk and uncertainty are the same. But they are not. Risk is known unknown. Uncertainties are unknown unknowns. Former U.S. secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld writes: “There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. These are things we don’t know we don’t know”.

But they are not. Risk is known unknown.

Uncertainties are unknown unknowns. Former U.S. secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld writes: “There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know.

There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. These are things we don’t know we don’t know”.

In the book “The Personal MBA” – Josh Kaufman writes, “Risks are known unknowns. If you’re planning to pick up a friend from the airport, the probability that their flight will arrive several hours late is a Risk – you know in advance that the arrival time can change, so you plan accordingly.

Uncertainty is unknown unknowns. You may be late picking up your friend from the airport because a meteorite demolishes your car an hour before you planned to leave for the airport. Who could predict that? You can’t reliably predict the future based on the past events in the face of Uncertainty”.

In the book “More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places” – Michael Mauboussin writes: “Risk has an unknown outcome, but we know what the underlying outcome distribution looks like.

Uncertainty also implies an unknown outcome, but we don’t know what the underlying distribution looks like. So games of chance like roulette or blackjack are risky, while the outcome of a war is uncertain. Frank H. Knight said that objective probability is the basis for risk, while subjective probability underlies uncertainty”.

In the book “The Signal and the Noise” – Nate Silver writes: “Risk, as first articulated by the economist Frank H. Knight in 1921, is something that you can put a price on. Say that you’ll win a poker hand unless your opponent draws to an inside straight: the chances of that happening are exactly 1 chance in 11.

This is risk.

It is not pleasant when you take a “bad beat” in poker, but at least you know the odds of it and can account for it ahead of time. In the long run, you’ll make a profit from your opponents making desperate draws with insufficient odds. Uncertainty, on the other hand, is risk that is hard to measure.

You might have some vague awareness of the demons lurking out there. You might even be acutely concerned about them. But you have no real idea how many of them there are or when they might strike. Your back-of-the-envelope estimate might be off by a factor of 100 or by a factor of 1,000; there is no good way to know.

This is uncertainty.

Risk greases the wheels of a free-market economy; uncertainty grinds them to a halt”.

In an interview with Safal Niveshak – Prof. Sanjay Bakshi tells: “Risk, as you know from Warren Buffett, is the probability of permanent loss of capital, while uncertainty is the sheer unpredictability of situations when the ranges of outcome are very wide. Take the example of oil prices. Oil has seen US$140 a barrel and US$40 a barrel in less than a decade.

The value of an oil exploration company when oil is at US$140 is vastly higher than when it is at US$40. This is what we call wide ranges of an outcome. In such situations, it’s foolish to use “scenario analysis” and come up with estimates like base case US$90, probability 60%, optimistic case US$140, probability 10%, and pessimistic case US$40, probability 30% and come up with weighted average price of US$80 and then estimate the value of the stock.

That’s the functional equivalent of a man who drowns in a river that is, on an average, only 4 feet deep even though he’s 5 feet tall. He forgot that the range of depth is between 2 and 10 feet”.

At the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, (http://usacac.army.mil/organizations/ufmcs-red-teaming) they teach under the premise that people and organizations around the country court failure in predictable ways.

This happens due to their mindsets, biases, and experience which are largely formed and molded by their culture and context. Decision-making, by its simplest definition, is the cognitive process of identifying a path to the desired outcome.

Cultural empathy and groupthink

Two areas of needed growth and identification in reaching these desired end states are fostering cultural empathy and groupthink. In an attempt to ask better questions and facilitate planning, policy making, and strategic and operational decision-making, one must foster cultural empathy; a better knowledge and understanding of the differences and similarities between our own culture and those held by others.

Irving Janis defines groupthink as, “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.” In other words, when working in a group, people have a tendency to adhere to the majority thought held within the room in an attempt to be a part of the group.

No one wants to be the outlier, but there always needs to be the one who plays “Devil’s Advocate” and test assumptions and present alternative perspectives to determine the course of action chosen is the right one. Groupthink has the ability to inhibit good decision-making within an organization.

Randomly Fragmented Clusters of Information, Often Contradictory, Can Lead to Flawed Decisions

As a result of information overload and the sheer volume of data available via social media and the Internet, we find ourselves dealing with randomly fragmented clusters of information that form the basis of our decision making.

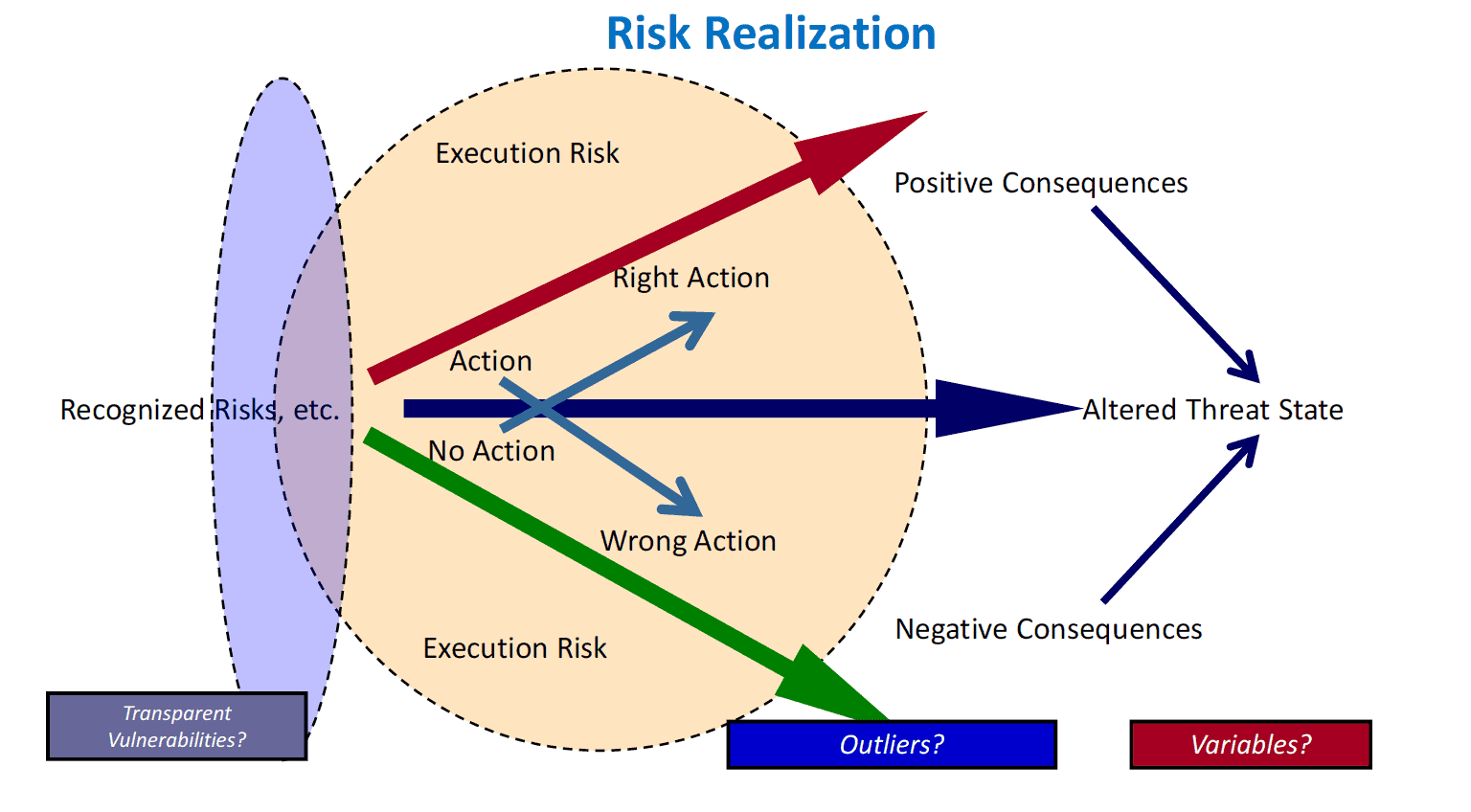

In essence, there is a lot of uncertainty involved in decision making. There is also a lot of uncertainty in assessing risks, threats, etc. As depicted in Figure 1, “Risk Realization”, one can readily see that any action you take to “buffer” the effects of a risk being realized is subject to a lot of uncertainty, outliers, transparent vulnerabilities and variables (recognized/unrecognized).

We must recognize that while we are going through the process of “risk buffering” so too are others who face the same risks. Hence whenever a change is made (i.e., “risk buffering” to offset risk realization) by one entity it affects all the other entities who share the risk within the same network.

Likelihood, Volatility, Velocity, and Impact need to be taken into account. “The Unpredictability of Uncertainty?” By Geary W. Sikich – Copyright© Geary W. Sikich 2016. World rights reserved. Published with permission of the author.

We live in a volatile changing environment full of uncertainties. When making assessments we need to embrace the concept of non-static risk and focus on attaining an altered threat state; that is getting to a continual process of risk buffering in order to keep the organization operating in a continuum that maintains a “risk parity” balance.

A World of Uncertainty Recognized Risks, etc. Action Right Action No Action Wrong Action Altered Threat State Positive Consequences Negative Consequences Execution Risk Execution Risk Variables? Outliers? Transparent Vulnerabilities? Risk Realization

One must make sense of the environment you are operating in. The Youtube video, “Did You Know 3.0 (Officially updated for 2012)” https://youtu.be/YmwwrGV_aiE provides a perspective on uncertainty.

Did You Know 2016 (https://youtu.be/uqZiIO0YI7Y) provides an excellent comparison of what has happened in 4 short years. An explosion of uncertainty.

Agility, ability to learn quickly and maintain an external focus while being aware of the internal machinations within your organization are critical to being responsive individually and collectively to the risks, threats, hazards, vulnerabilities and the velocity, impact that these will have if realized (likelihood of happening).

Tackling Uncertainty

What does it take to tackle uncertainty? Ask yourself this question: “Does my organization have a “fixed mindset” or do we have a “learning mindset”?

Now, ask yourself the same question.

What is needed today in the face of uncertainty is agility, a learning mindset, and an external focus. Peter Drucker said, “90% of the information used in organizations is internally focused and only 10% is about the outside environment. This is exactly backwards.”

Drucker’s statement is worth looking at within the context of your own organization. Are you trapped in a web of internal focus, making assumptions about the external environment without any corresponding validation of the accuracy of these assumptions?

Risk assessments are a best guess at what (risk, threat, vulnerability, hazard, business impact, etc.) might befall an organization. The plans we develop to address “The What” are a best guess at the anticipated reaction to an event.

You cannot predict the future

You need to avoid anchoring on assessments and plans as you cannot forecast actual outcomes. “The Unpredictability of Uncertainty?” By Geary W. Sikich – Copyright© Geary W. Sikich 2016. World rights reserved. Published with permission of the author.

“We’re living in a world where we need to completely understand our environment and then look for anomalies, look for change and focus on the change“ — Admiral Mike Mullen, 17th Chair, Joint Chiefs of Staff. This is a fascinating comment and a great sound bite. But if you begin to dissect it, you find the impossibility of the statement.

First, can you completely understand your environment?

Second, how will I know what anomalies to look for?

What parameters, metrics, indicators, etc., do I put in place to determine an anomaly? And, since change is occurring so rapidly what should I focus on? Am I going to be looking in the rearview mirror as I move forward? Am I flying behind the plane in It wake and turbulence?

What’s needed and where do we find a balance?

Deborah Amcona, PhD., MIT recently presented a webinar entitled, “Leading in an Uncertain World”. She presented four leadership capabilities that need to be present in a distributed leadership organization:

- Visioning – the ability to be future focused;

- Relating – the ability to create trust among the team;

- Inventing – the ability to be agile in the current environment (i.e., alternative analysis);

- Sense making – Carl Weik defines sense making as the process by which people give meaning to experience (see addendum to this article and Wikipedia for more).

These four traits should be present in every risk, threat, hazard, vulnerability and business impact assessment, etc. that your organization undertakes.

Concluding Thoughts

Risk, threat, hazard, vulnerability, business impact, etc., assessments are tools generally created with set categories and fixed metrics (checklists, etc.) that advocate how to conduct an assessment and what is expected in the post-assessment report.

This rigid framework reduces the flexibility necessary to create a meaningful assessment. Due to Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity (VUCA) and the concept of Likelihood, Impact, and Velocity (LIV) there is a greater need to understand the non-static nature of risk, etc. and the impact on the validity of our assessments.

In the October 2016 Issue of the Harvard Business Review an article entitled, “Noise: How to Overcome the High, Hidden Cost of Inconsistent Decision Making” by Daniel Kahneman Andrew M. Rosenfield Linnea Gandhi Tom Blaser stated:

“The problem is that humans are unreliable decision makers; their judgments are strongly influenced by irrelevant factors, such as their current mood, the time since their last meal, and the weather. We call the chance variability of judgments noise”.

Nassim Taleb, famous for his book “The Black Swan”, has created a cadre of people (not necessarily associated with Taleb) who claim to be “Black Swan Hunters”.

One look at Taleb’s definition should cause you to pause when one of the “Black Swan Hunters” begins to pontificate on finding Black Swans. The definition for those who have never heard it is:

“A black swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable than it was.”

There is a general lack of knowledge when it comes to rare events with serious consequences. This is due to the rarity of the occurrence of such events. In his book, Taleb states that “the effect of a single observation, event or element plays a disproportionate role in decision-making creating estimation errors when projecting the severity of the consequences of the event. The depth of consequence and the breadth of consequence are underestimated resulting in surprise at the impact of the event.”

To quote again from Taleb, “The problem, simply stated (which I have had to repeat continuously) is about the degradation of knowledge when it comes to rare events (“tail events”), with serious consequences in some domains I call “Extremistan” (where these events play a large role, manifested by the disproportionate role of one single observation, event, or element, in the aggregate properties).

I hold that this is a severe and consequential statistical and epistemological problem as we cannot assess the degree of knowledge that allows us to gauge the severity of the estimation errors.

Alas, nobody has examined this problem in the history of thought, let alone try to start classifying decision-making and robustness under various types of ignorance and the setting of boundaries of statistical and empirical knowledge.

Furthermore, to be more aggressive, while limits like those attributed to Gödel bear massive philosophical consequences, but we can’t do much about them, I believe that the limits to empirical and statistical knowledge I have shown have both practical (if not vital) importance and we can do a lot with them in terms of solutions, with the “fourth quadrant approach”, by ranking decisions based on the severity of the potential estimation error of the pair probability times consequence“ (Taleb, 2009; Makridakis and Taleb, 2009; Blyth, 2010, this issue).

Uncertainty is all about unpredictability.

You cannot determine the probability of uncertainty, just as you cannot predict when a “Black Swan” event will occur; let alone name the event that will be known as a “Black Swan”.

It is more prudent to ensure that the organization has the resilience to withstand events of any magnitude (think “worst case scenarios”) and that the organization has the processes in place to identify indicators for early warning.

A bit of Sense making should guide us as we work through the compliance requirements, fixed framework, categories and generally “tactical” focus in assessment and decision-making procedures.

Bio:

Geary Sikich – Entrepreneur, consultant, author and business lecturer

Contact Information: E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com. Telephone: 1- 219-922-7718.

Geary Sikich is a seasoned risk management professional who advises private and public sector executives to develop risk buffering strategies to protect their asset base. With an M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance, Geary’s focus is human capital: what people think, who they are, what they need and how they communicate.

With over 25 years in management consulting as a trusted advisor, crisis manager, senior executive and educator, Geary brings unprecedented value to clients worldwide. Geary has written 4 books (available on the Internet) over 390 published articles and has developed over 4,000 contingency plans for clients worldwide.

Geary has conducted over 350 workshops, seminars and presentations worldwide. Geary is well-versed in contingency planning, risk management, human resource development, “war gaming,” as well as competitive intelligence, issues analysis, global strategy and identification of transparent vulnerabilities.

Geary began his career as an officer in the U.S. Army after completing his BS in Criminology. As a thought leader, Geary leverages his skills in client attraction and the tools of LinkedIn, social media and publishing to help executives in decision analysis, strategy development, and risk buffering.

A well-known author, his books and articles are readily available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and the Internet.

References

Apgar, David, “Risk Intelligence – Learning to Manage What We Don’t Know”, Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

Davis, Stanley M., Christopher Meyer, “Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy”, (1998

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply