In Part 1 of Beyond the Numbers, I reflected on why Human Factors matter in reliability engineering and how the human element of the system can be overlooked by traditional hardware-focussed approaches.

This article explores how Human Factors principles can be integrated into traditional reliability analyses such as Reliability Block Diagrams (RBDs), Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) and Failure Mode, Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) and without reinventing the wheel or introducing additional complexity.

The short answer is that we are already doing much of this implicitly. Applying Human Factors principles makes those assumptions explicit and therefore visible, challengeable and open to improvement.

Human Performance Assumptions

Reliability practitioners should already be comfortable in dealing with uncertainty. We routinely estimate failure rates from incomplete data, apply confidence limits and accept that models are approximations of reality rather than perfect representations.

Yet when it comes to human performance, we often default to a silent assumption that the human will do the right thing, at the right time, every time. This assumption is rarely stated, rarely challenged and rarely justified.

In practice however, many of the systems we model rely on people to:

- Perform system configuration or start-up actions

- Diagnose faults and select recovery actions

- Restore redundancy following failures

- Execute maintenance tasks correctly and completely

If those actions are not performed, or not performed in the way that was envisaged, the modelled reliability may never be realised in operation.

Reliability Block Diagrams: Hardware Modelling to Functional Success

RBDs are widely used to represent how system functions depend on combinations of components. They are often interpreted as hardware models, but in reality they model functional success paths and many of those paths include human action, examples include:

- Manual switching between redundant paths

- Operator-initiated reconfiguration

- Fault acknowledgement and reset actions

- Human-dependent restoration of failed items

In many models, these actions are assumed to be instantaneous and perfectly reliable.

Making human dependency visible

A practical first step is to represent human-dependent actions explicitly:

- Introduce blocks representing critical human tasks

- Assign task success probabilities

- Explore sensitivity rather than precision

The intent is not to define precise human error probabilities, but to understand how dependent system success is on human performance.

For example, a system may appear highly resilient due to redundancy, but if both paths rely on the same human action under time pressure, the functional reliability may be far more fragile. The RBD below first presented in Part 1, illustrates this example:

Taking this approach leads to better design questions:

- Can this critical dependency be removed or designed out?

- Can a manual task be automated or simplified?

- Are there conditions where the failure of this action becomes unacceptable?

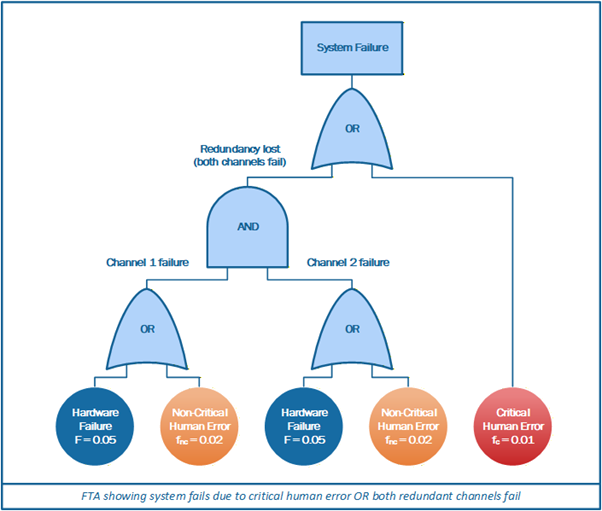

Fault Tree Analysis: Human Errors as Basic Events

FTA represents combinations of events that lead to an undesired outcome. There is no technical reason why human actions cannot be represented as basic events, yet in practice they are often excluded or oversimplified.

The following Fault Tree re-expresses the previous RBD in failure logic terms, treating human actions in the same way as technical failures. For practitioners, the value lies less in the precise numbers and more in the visibility this provides into where human actions meaningfully influence system risk and where changes to design, procedures, or training may have the greatest impact.

Practical integration

Human actions can be modelled as:

- Failure to respond to an alarm

- Incorrect diagnosis leading to wrong action

- Failure to complete a required recovery step

Where data is limited (which it often is), conservative probability ranges can be used, or qualitative sensitivity studies performed.

The value lies not in the exact number, but in understanding:

- Whether human performance dominates the risk

- How sensitive the outcome is to task difficulty or context

- Where design or procedural changes would have the greatest benefit

FTA becomes a powerful tool for challenging optimistic assumptions about human performance, particularly in time-critical or high-stress scenarios.

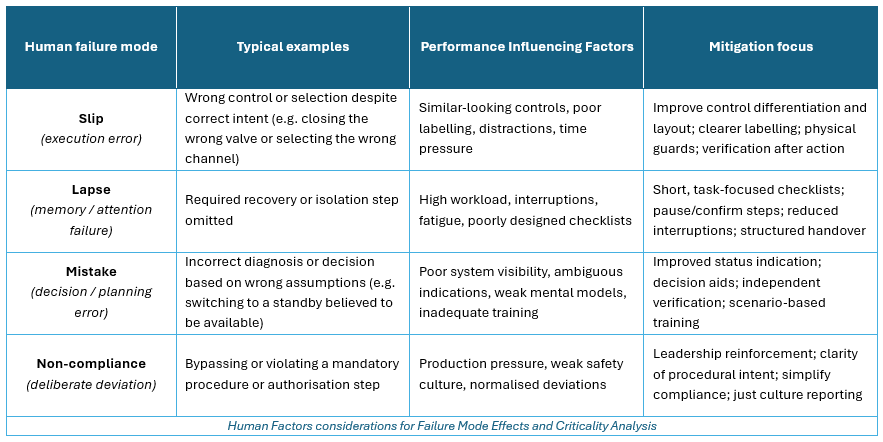

Failure Mode, Effects and Criticality Analysis: Integrating Human Actions

FMECA is a familiar and trusted technique for understanding how systems can fail and for prioritising mitigation. Traditionally, failure modes are associated with hardware or software items. However, people also fail in identifiable and predictable ways and there is no technical reason why human actions cannot be represented within the same analytical framework.

Applying FMECA thinking to human activity does not require a new method. It requires recognising that human performance is shaped by task design, interfaces, procedures and operating context and that these factors can be analysed just as systematically as technical causes.

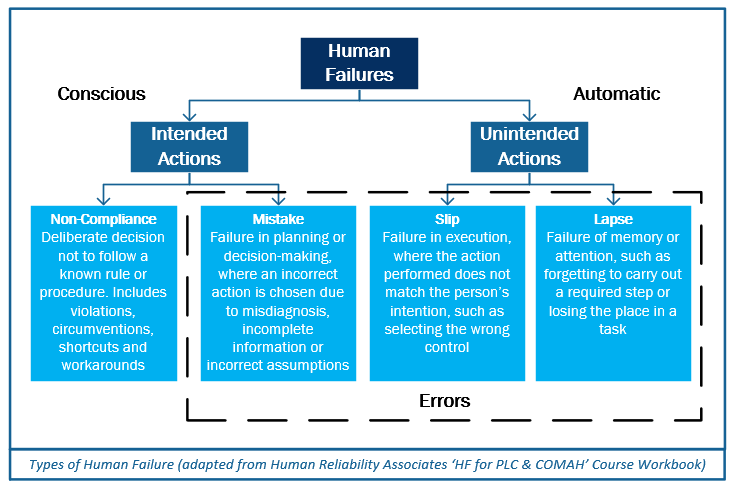

Types of human failure

Human failure modes can be grouped in a simple and practical way, based on whether the action was intended or unintended and whether the resulting behaviour reflects a deliberate choice, a planning or decision-making error, or a breakdown in execution or memory, as illustrated in the diagram below:

Crucially, these failure modes are not attributes of individuals. They arise from the way tasks are designed, information is presented, procedures are written and work is carried out under real operating conditions.

Integrating human failure modes into FMECA

When human actions are treated as potential failure modes within a FMECA, the intent is not to list every possible error, but to understand how human performance can influence system outcomes and where mitigation effort is most effective. Rather than conducting a separate analysis, human failure modes can be:

- Included alongside technical failure modes, rather than treated separately

- Linked directly to specific tasks, interfaces, or decisions

- Assessed using the same severity, occurrence, and detectability logic familiar to practitioners

This shifts the focus away from assigning “operator error” as a cause and towards identifying the Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs) that shape human performance, such as workload, interface design, time pressure, or procedural ambiguity.

In turn, this allows mitigation actions to focus on design changes, procedure and interface improvements, training or task restructuring, rather than relying solely on behavioural controls or additional rules.

The table below provides an illustrative example of how different types of human failure can be represented within a FMECA, linking typical examples with relevant PIFs and potential mitigation approaches:

Key takeaway

Human failure modes can be analysed, prioritised and mitigated using the same reliability thinking as hardware failures. The difference lies not in the method, but in recognising that people operate within systems and it is those systems that most strongly shape reliability outcomes.

Avoiding False Precision

A common concern when discussing human reliability is the fear of false accuracy and assigning spurious numbers to complex human behaviour.

This concern is valid – but it is not a reason to ignore the issue entirely.

Reliability models already contain uncertainty:

- Failure rates are often based on sparse data

- Environmental and usage assumptions are idealised

- Human performance is frequently assumed to be perfect by default

Replacing an unstated assumption of perfection with a transparent, bounded assumption of fallibility is an improvement, not a regression. The aim is not to predict human behaviour precisely but to design systems that are robust to human variability.

Incremental Integration, Not Reinvention

One of the most important lessons from my own learning is that integrating human reliability does not require a wholesale change to established practice.

It can start incrementally:

- Identifying where models depend on human action

- Making those dependencies visible

- Challenging whether assumptions are realistic

- Using sensitivity and scenario thinking rather than precision

Traditional reliability methods remain essential. Integrating human reliability simply extends their relevance to the socio-technical systems we are actually designing, operating and maintaining.

Closing Reflection

Reliability models are not just mathematical interpretations they are expressions of how we believe systems will behave in the real world. When we ignore the human contribution, we risk creating models that are technically sound but operationally fragile.

By integrating human reliability principles into RBDs, FTA and FMECA, we move towards models that better reflect reality, not because they are more complex, but because they are more explicit about system vulnerabilities

Reliability engineering does not stop at understanding how systems fail. Through processes such as Reliability Centred Maintenance (RCM), it directly shapes how maintenance is derived and how tasks are ultimately performed.

In the next part of this series, I will move from reliability-focussed tools to the maintenance domain, exploring how Human Factors principles can be integrated into RCM and Maintenance Task Analysis (MTA) and why realistic assumptions about human performance are just as important when defining maintenance as they are when predicting failure.

I’d be interested to hear from others working in reliability, maintainability and supportability engineering across defence and related sectors:

- Where do your models already depend on human performance, and how is that dependency made visible or communicated?

… and for Human Factors practitioners:

- Where do you see opportunities to influence traditional reliability analysis more directly and proportionately?

I’d be genuinely interested to hear others’ perspectives…

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply