Guest Post by Geary Sikich (first posted on CERM ® RISK INSIGHTS – reposted here with permission)

Introduction

We are enamored by risk models, mathematic algorithms, equations and formulae. As a matter of fact, we have become so enamored by complex mathematical algorithms, formulas, models and derivatives that we have abdicated much of the analysis of risk, to these complex formulas and quantitative analysis methodologies touted by firms far and wide. Where has this gotten us? Are we better able to predict and measure risk exposures? Are we managing risk more effectively?

For all the modeling and application of mathematical formula, our ability to predict, analyze and manage risk is really not that much improved. This is due, in part, to our lack of understanding risk. Risk does not cause harm. The impact of risk realization is what causes harm. And, the impact cannot be applied universally to all organizations. Risk realization impacts every entity in its own unique manner.

Risk Modeling: Limitations or Inhibitions

Risk models are increasingly becoming a crutch for risk managers allowing them to once again abdicate responsibility and entrust all to the risk model. Risk models used to determine the potential effects of risk are popular and their use continues to grow. However, in his article, entitled, “Accounting and Risk Management: the need for integration,” (Brendon Young, Journal of Operational Risk, Vol.6, Number 1, Spring 2011) the lead section is entitled “The Failure of Risk Management is Symptomatic of Wider Intellectual Failure.” Mr. Young cites numerous studies and authorities, saying that “many risk professionals no longer believe that the principles of risk management are sound.” It appears from this article and citations that there is a growing lack of confidence in risk management systems.

Considerable benefits have been derived from the use of risk models. However, as we make our risk models more complex by incorporating features such as feedback loops and decision theory, that attempt to anticipate/take into account management responses some readily apparent limitations begin to bubble to the surface. For example, a severe global pandemic would not only cause the loss of lives but potentially a far greater risk of interdicting global supply chains, bypassing all risk management models and efforts. As an adjunct to this example, but related to the supply chain, a disruption of corn production due to supply chain disruption could create untold problems. The whole problem with risk modeling is the scope of challenges that cannot be incorporated into the models because they are simply unthinkable. I will highlight some limitations that need to be taken into account:

- Incompleteness of the model

- Incorrectly specified parameters/scope

- Overly complex

- Scenarios may no longer be appropriate

- Obsolescence of the risk model

- High cost to develop, operate and maintain

- Require a high degree of interpretational skill (knowledge, experience, background – human capital)

The reaction to the financial crisis was to increase regulation, a legislative knee jerk reaction to crisis. More regulation will not solve the issues related to our over dependence on risk models, mathematic algorithms, equations and complex formulae. To paraphrase Darwin, “it is not the strongest of the species that survives, not the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.”

The Human Factor

Through the use of arbitrary scales, we humans have established standards that we feel are scientifically valid and based on what we assume is reasonableness. Is this arrogance or being naïve? How can we put limits – arbitrary limits at that – on natural events, markets, geopolitical systems, human nature? Every time we set an arbitrary scale, we limit our ability to comprehend and manage risk. Of the 800+ tsunamis that occur in the Pacific Ocean approximately 22% (176) impact the coast of Japan. Why is it that when one hits, that is off the scale of our risk perception do we suddenly raise the alarm that we must plan for tsunamis? Japan is seismically active with over 1,000 earthquakes recorded annually. Yet, Japan is not the most active seismic area in the world. The New Madrid Fault in the central United States records more earth movement. Yet, we do not hear a great cry for earthquake planning in the central United States. Rather, we hear a whisper that something should be done.

Because we are human, we generally can only relate to that which we have experienced. Therefore, if I have not experienced the unexpected (it being beyond my experience), how can I plan effectively for what I do not know? How can I develop a risk model that anticipates unexpected eventualities as I do not have the capability to model them, because I cannot think of them! We can make assumptions; but assumptions are at best, a best guess of what we think might happen or what could be a scale that we are comfortable with. Perception is our reality. For example, in differential calculus, an inflection point, point of inflection or inflection (inflexion) is a point on a curve at which the curvature changes sign. Observing the curve change from being concave upwards (positive curvature) to concave downwards (negative curvature), or vice versa is not a static proposition. If one imagines driving a vehicle along a winding road, inflection is the point at which the steering-wheel is momentarily “straight” when being turned from left to right or vice versa. The change in direction is based on our perception influenced by our visual capacity to determine a change in direction.

It is the same with the “Bell Curve.” A typical Bell Curve depicts a normal distribution in most cases. However as with the inflection point, the Bell Curve is a static representation applied to a fluid world. They are not reflective of reality, but rather represent our best estimation of a “snapshot of time.” In reality a Bell Curve would have to be seen as vibrating or demonstrating resonance; not being static is a fact of life. The same holds true for inflection points, as is demonstrated in the steering wheel example. Most of us have a difficult time visualizing this resonance. That is due primarily to our inherent diagnostic biases.

A diagnostic bias is created when four elements combine to create a barrier to effective decision making. Recognizing diagnostic bias before it debilitates effective decision making can make all the difference in day-to-day operations. It is essential to developing and managing a robust and resilient enterprise risk management program that diagnostic biases are recognized and taken into account to avert compounding initial modeling errors. The four elements of diagnostic bias are:

- Labeling

- Loss Aversion

- Commitment

- Value Attribution

Labeling creates blinders; it prevents you from seeing what is clearly before your face – all you see is the label. Loss aversion essentially is how far you are willing to go (continue on a course) to avoid loss. Closely linked to loss aversion, commitment is a powerful force that shapes our thinking and decision making. Commitment takes the form of rigidity and inflexibility of focus. Once we are committed to a course of action it is very difficult to recognize objective data because we tend to see what we want to see; casting aside information that conflicts with our vision of reality. First encounters, initial impressions shape the value we attribute and therefore shape our future perception. Once we attribute a certain value, it dramatically alters our perception of subsequent information even when the value attributed (assigned) is completely arbitrary.

Recognize that we are all swayed by factors that have nothing to do with logic or reason. There is a natural tendency not to see transparent vulnerabilities due to diagnostic biases. We make diagnostic errors when we narrow down our field of possibilities and zero in on a single interpretation of a situation or person. While constructs help us to quickly assess a situation and form a temporary hypothesis about how to react (initial opinion) they are restrictive in that they are based on limited time exposure, limited data and overlook transparent vulnerabilities.

The best strategy to deal with disoriented thinking is to be mindful (aware) and observe things for what they are (situational awareness) not for what they appear to be. Accept that your initial impressions could be wrong. Do not rely too heavily on preemptive judgments; they can short circuit more rational evaluations. Are we asking the right questions? When was the last time you asked, “What Variables (outliers, transparent vulnerabilities) have we Overlooked?”

My colleague, John Stagl adds the following regarding value. Value = the perception of the receiver regarding the product or service that is being posited. Value is, therefore, never absolute. Value is set by the receiver.

Some thoughts:

- If your organization is content with reacting to events it may not fair well

- Innovative, aggressive thinking is one key to surviving

- Recognition that theory is limited in usefulness is a key driving force

- Strategically nimble organizations will benefit

- Constantly question assumptions about what is “normal”

Ten blind spots:

#1: Not Stopping to Think

#2: What You Don’t Know Can Hurt You

#3: Not Noticing

#4: Not Seeing Yourself

#5: My Side Bias

#6: Trapped by Categories

#7: Jumping to Conclusions

#8: Fuzzy Evidence

#9: Missing Hidden Causes

#10: Missing the Big Picture

KISS vs. KICD

We are all familiar with the term “KISS” (Keep It Simple Stupid); and we hear a lot about how we should strive to simplify things. What, in fact, is happening though is exactly the opposite. “KCID” (Keep It Complicated and Difficult) is becoming the new norm. KCID is creating more brittle, risk susceptible infrastructures, systems and enterprises. As things grow in complexity they become less flexible rather than more flexible. Complexity means that within a network of entities, a reaction by one entity will have unexpected effects on the entire network’s touchpoints. Five key assumptions form the basis for KICD:

- Assumption # 1: The modern business organization and/or governmental organization represents a complex system operating within multiple networks

- Assumption # 2: There are many layers of complexity within an organization and its “Value Chain”

- Assumption # 3: Due to complexity, active analysis of the risk, potential consequences of disruptive events, etc. is critical

- Assumption # 4: Actions in response to events affecting entities within the system needs to be coordinated

- Assumption # 5: Resources and skill sets are key issues as they are limited and becoming more specialized

Based on the above assumptions we can see that complexity in and of itself is a risk that needs to be analyzed and monitored by every organization.

What exactly are all these swans we keep hearing about and what do they mean?

We hear a lot about events that are being labeled “Black Swans” thanks to Nassim Taleb and his extremely successful book, “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable,” now in its second edition. I have written several articles centering on the “Black Swan” phenomenon; defending, clarifying and analyzing the nature of “Black Swan” events. And, I am finding that wildly improbable events are becoming perfectly routine events.

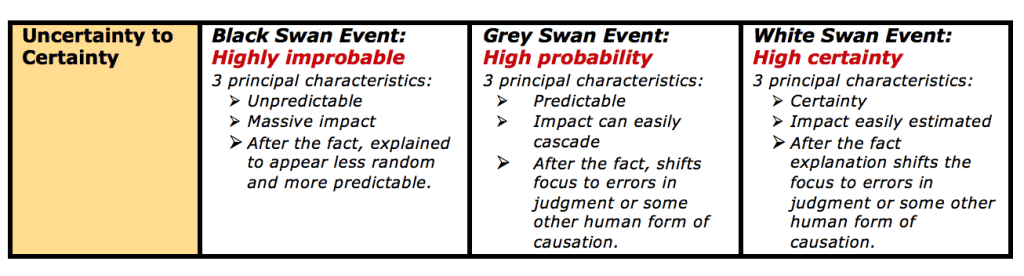

Nassim Taleb provides the answer for one of the Swans in his book “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable.” He states that a Black Swan Event is:

A black swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.

Taleb continues by recognizing what he terms the problem –

“Lack of knowledge when it comes to rare events with serious consequences.”

The above definition and the recognized problem are cornerstones to the argument for a serious concern regarding how risk management is currently practiced. However, before we go too far in our discussion, let us define what the other two swans look like.

A grey swan is a highly probable event with three principal characteristics: it is predictable; it carries an impact that can easily cascade; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that recognizes the probability of occurrence, but shifts the focus to errors in judgment or some other human form of causation.

I suggest that we tend to phrase the problem thus –

“Lack of judgment when it comes to high probability events that have the potential to cascade.”

Now for the “White Swan”

A white swan is a highly certain event with three principal characteristics: it is certain; it carries an impact that can easily be estimated; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that recognizes the certainty of occurrence, but again, shifts the focus to errors in judgment or some other human form of causation.

I suggest that we tend to phrase the problem thus –

“Ineptness and incompetence when it comes to certainty events and their effects.”

The table below sums up the categorization of the three swan events.

Taleb uses the example of the recent financial crash as a “White Swan” event. In a video about risk and robustness, Taleb talks with James Surowiecki of the New Yorker, about the causes of the 2008 financial crisis and the future of the U.S. and by default the global economy. A link to the video follows: http://link.brightcove.com/services/player/bcpid1827871374?bctid=90038921001

We should begin to rethink the concept of the “Black Swan.” A Black Swan is a metric that is infinite. Once you have experienced a “Black Swan” event subsequent events that are similar are no longer Black Swans. Rather, the metric for the categorization of an event as a Black Swan has been raised to a higher level of measurement. Earthquakes are a good example, just because we have a metric scale for severity of earthquakes, does not preclude the occurrence of an earthquake of a magnitude that is higher than the current scale. We set arbitrary limitations. These arbitrary limitations facilitate the current definition of what a “Black Swan” is. Essentially, we are wrong in confining ourselves to these arbitrary limitations.

More “White Swans” (Certainty) does not mean full speed ahead

Risk is complex. When risk is being explained, we often have difficulty listening and comprehending the words used in the explanation. Why? The rather simple explanation is: compelling stories are most often told with dramatic graphics! Molotov Cocktails, RPG-7’s and riots are interesting stuff to watch; no matter that the event has occurred elsewhere and may be totally meaningless to you. Is this pure drama or are these events that we should be concerned about? Or are they so unusual and rare that we fail to comprehend the message about the risks that we face?

Communication and how we communicate is a key factor. Words by themselves are about 7% effective as a communication tool. Words, when coupled with voice tonality raise effectiveness to about 38%. However, the most effective way to communicate is via physiology, which gets us to about 55% effective. Well, the next best thing to being there is being able to see what is there. Hence the effectiveness of graphics that evoke drama, physiology and raise emotions in communicating your message! The quote that a picture is worth a thousand words has never been so true as it is today.

Ideas get distorted in the transmission process. We typically remember:

- 10% what we hear

- 35% what we see

- 65% what we see & hear

Yet, we typically spend:

- 30% speaking

- 9% writing

- 16% reading

- 45% listening

We live in an era of information explosion and near instantaneous availability to this information. Driven by a media bias for the dramatic we are constantly being informed about some great calamity that has befallen mankind somewhere in the world. The BP disaster in the Gulf of Mexico has been eclipsed by flooding in Pakistan, which will get eclipsed by some other catastrophe.

Society is not awash with disasters! There is always another flood, riot, car bomb, murder, financial failure just around the corner. And, there is a compelling reason for this! The societies we live in have a lot of people! Some quick examples – China and India each have over 1 billion people. The U.S. has 300 million people. The European Union has 450 million people. Japan has 127 million people.

With this many people around, there would appear to be a bottomless supply of rare, but dramatic events to choose from. Does this seemingly endless parade of tragedy reflect an ever dangerous world? Or, are the risks overestimated due to the influence of skewed images?

Taleb tells us that the effect of a single observation, event or element plays a disproportionate role in decision-making creating estimation errors when projecting the severity of the consequences of the event. The depth of consequence and the breadth of consequence are underestimated resulting in surprise at the impact of the event. Theories fail most in the tails; some domains are more vulnerable to tail events.

Question # 1: How much would you be willing to pay to eliminate a 1/2,500 chance of immediate death?

I ask this question as a simple way to get an understanding of where your perception of risk is coming from. Is it logical and rational or is it emotional and intuitive? Ponder the question as you read the rest of this piece.

Risk, Risk Perception, Risk Reality

When we see cooling towers, our frame of reference generally will go to nuclear power plants. More specifically, to Three Mile Island, where America experienced its closest scare as a result of a series of errors and misjudgments. As you can see a cooling tower is nothing more than a large vent that is designed to remove heat from water (what is termed “non-contact water) used to generate steam.

We worry about cooling towers spewing forth radioactive plumes that will cause us death – when, in fact, this cannot happen. Yet we regularly board commercial airliners and entrust our lives to some of the most complex machinery man has created!

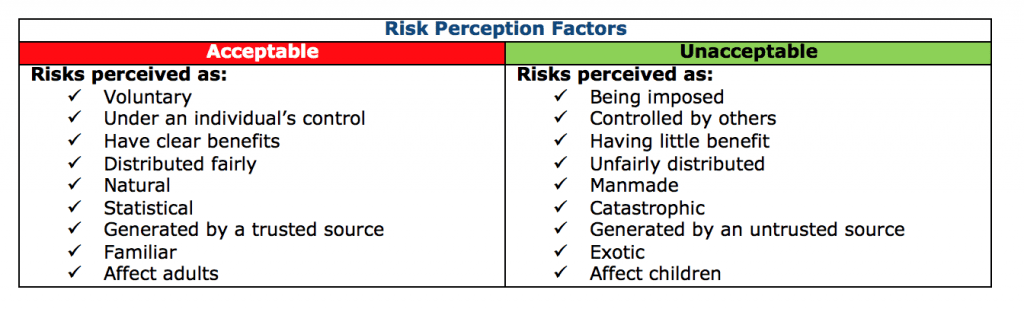

Our perceptions of risk are influenced by several factors. Peter Sandman, Paul Slovic and others have identified many factors that influence how we perceive risk. For example:

People perceive risks differently; people do not believe that all risks are of the same type, size or importance. These influencing factors affect how we identify, analyze and communicate risk. Why is it so important to effectively communicate risk information? Here are a few vivid examples of how poor communication/no communication turned risk realization into brand disasters:

- Firestone Tire Recall – Destroys a 100 year relationship with Ford

- Exxon Valdez Oil Spill – Still getting press coverage after 20 years

- Coke Belgium Contamination – Loss of trust

- BP Deepwater Horizon – Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) restructured?

Many years ago, I attended a conference on risk and risk communication in Chicago in the aftermath of the Bhopol disaster in India. Peter Sandman was one of the speakers and he left an indelible imprint on my brain that has stood the test of time and the test of validation. He drew the following equation:

RISK = HAZARD + OUTRAGE

Sandman, explained his equation as follows:

“Public perception of risk may not bear much resemblance to Risk Assessment. However, when it comes to their accepting risk one thing is certain; perception is reality.”

Sandman concluded his presentation with the following advice regarding the six interrogatories:

- WHO: Identify internal/external audiences

- WHAT: Determine the degree of complexity

- WHY: Work on solutions – not on finger pointing

- WHEN: Timing is critical

- WHERE: Choose your ground – know your turf

- HOW: Manner, method, effectiveness

In the 20+ years since that speech in Chicago much has changed. Social Media has, will, might; transform our lives – take your choice. While I agree that the Internet has transformed the lives of millions; I am not convinced that it has yet displaced the traditional media sources for our news. One issue that is yet to be resolved is “how trustworthy the source.”

Information, especially information found via social networking, social media, etc., requires significant insight and analysis. Beyond that, confirmation of the source is critical. Can you imagine the above story making its way into the legal proceedings under discovery?

Now in its second year, the Digital Influence Index created by the public relations firm, Fleishman-Hillard Inc. covers roughly 48% of the global online population, spanning France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, China, Japan, and the United States. With less than 50% coverage (62% of the global online population is not reflected in the Digital Influence Index) they would have you believe that the index is a valid indicator of the ways in which the Internet is impacting the lives of consumers.

Many years ago I was provided with some insight as I developed a crisis communications program for another major oil company. While attending a presentation on crisis communications eight guiding principles were offered. I think that they are still very valid today:

| ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY | THINK IN TERMS OF BROAD DEFENSE |

| LOOK LIKE YOU CARE AND MEAN IT | RELY ON RESEARCH |

| DON’T WORRY ABOUT BEING SUED | BEWARE OF EXPERTS |

| DO THE RIGHT THING | THERE IS NO MAGIC BULLET |

Management is never put more strongly to the test than in a crisis situation. The objectives are immediate and so are the results. A crisis is an event requiring rapid decisions involving the media that, if handled incorrectly, could damage your company’s credibility and reputation.

Risk perception will influence your ERM program. Management simply must devote sufficient resources to recognizing and understanding how operations are being viewed from a risk perspective. With routine incidents being treated as front‑page news by the media, you must be prepared to deal with public perception, as well as reality.

Disruptive (Unsettling) by Design (with Purpose, Plan, Intent)

How can you get better at anticipating what will happen? That is the million dollar question. What do you need to do to create an ERM program that leverages forward and creates global awareness within your organization? You must learn to create a mosaic from diverse sources of information and diverse elements within your enterprise. You must learn how to respond to change, disruption and uncertainty; and how to use disruption and uncertainty to your advantage to create a business continuity plan that is truly resilient. Disruption is transforming the way smart organizations make decisions, keeping their business in business when faced with disruptive events. For example, here might be a typical sequence of events:

A risk materializes or is realized (event occurs). Someone, who is perceived to have good information and/or insight into the event or problem, makes a decision. Others observing the first person’s decision avoid further analysis/discovery and copy the earlier decision. The more people that copy the earlier decision, the less likely any new discovery or analysis will occur. If the earliest decision was correct, everything works out. If it was not, the error is compounded, literally cascading throughout the organization.

Modern communications systems allow information to cascade rapidly; exacerbating the effect of a wrong or inadequate decision. Disruption happens. Natural disasters, technology disasters, manmade disasters happen. How would a technology breakthrough, a shift in consumer demand or a rise, or fall, in a critical market affect the continuity of your business? Any of these can rewrite the future of a company – or a whole industry. If you haven’t faced this moment, you may soon. It’s time to change the way you think about continuity and the way you run your business.

How you decide to respond is what separates the leaders from the left behind. Today’s smartest executives know that disruption is constant and inevitable. They’ve learned to absorb the shockwaves that change brings and can use that energy to transform their companies and their careers

Imagine that your ERM program has been implemented as it was designed. You and your organization carried out ERM implementation following every detail contained in the policy, planning documents and applicable protocols. Your ERM program has failed. That is all you know. Your ERM program failed.

Now your challenge and that of your ERM team is to explain why they think that the ERM program failed. You must determine how much contrary evidence (information) was explained away based on the theory that the ERM program you developed will succeed if you implement the steps required to identify and respond to risks to your business operations.

The goal of this type of exercise is to break the emotional attachment to the success of the ERM program. When we create an ERM program we become emotionally attached to its success. By showing the likely sources of breakdown that will impede and/or negate the ERM program (failure), we utilize a methodology that allows us to conduct a validation of the ERM program by determining the potential failure points that are not readily apparent in typical exercise processes.

ERM programs are based on a set of background assumptions that are made consciously and unconsciously. Risk materializes and seemingly without warning, quickly destroys those assumptions. The ERM program is viewed as not good and in need of complete overhaul. The collapse of assumptions is not the only factor or prominent feature that defines failure point exercise methodology; but it is without doubt, one of the most important.

Decision scenarios allow us to describe forces that are operating to enable the use of judgment by the participants. The Failure Point Methodology, developed by Logical Management Systems, Corp., allows you to identify, define and assess the dependencies and assumptions that were made in developing the ERM program. This methodology facilitates a non-biased and critical analysis of the ERM program that allows planners and the ERM Team to better understand the limitations that they may face when implementing and maintaining the program.

Developing the exercise scenario for the Failure Point Methodology is predicated on coherence, completeness, plausibility and consistency. It is recognized at the beginning of the scenario that the ERM program has failed. It is therefore not really necessary to create an elaborate scenario describing catastrophic events in great detail. The participants can identify trigger points that could create a reason for the ERM program to fail. This methodology allows for maximizing the creativity of the ERM Team in listing why the program has failed and how to overcome the failure points that have been identified.

This also is a good secondary method for ensuring that the ERM Team is trained on how the program works and that they have read and digested the information contained in the program documentation.

As it is often the case that the developers are not the primary and/or secondary decision makers within the program; and that the primary decision makers within the program often have limited input during the creation of the program (time limited interviews, response to questionnaires, etc.).

This type of exercise immerses the participants in creative thought generation as to why the ERM program failed. It also provides emphasis for ownership and greater participation in developing the ERM program. Senior management and boards can benefit from periodically participating in Failure Point exercises; one output being the creation of and discussion about thematic risk maps. As a result of globalization, there is no such thing as a “typical” failure or a “typical” success. The benefits of Failure Point exercises should be readily apparent. You can use the exercise process to identify the unlikely but potentially most devastating risks your organization faces. You can build a monitoring and assessment capability to determine if these risks are materializing. You can also build buffers that prevent these risks from materializing and/or minimize their impact should the risk materialize.

Managing “White Swans” – Dealing with Certainty

There are two areas that need to be addressed for Enterprise Risk Management programs to be successful. Both deal with “White Swans” (certainty). The first is overcoming “False Positives” and the second is overcoming “Activity Traps.”

A “False Positive” is created when we ask a question and get an answer that appears to answer the question. In an article, entitled Disaster Preparedness, featured in CSO Magazine written by Jon Surmacz August 14, 2003, it was written that:

“two-thirds (67 percent) of Fortune 1000 executives say their companies are more prepared now than before 9/11 to access critical data in a disaster situation.”

The article continued:

“The majority, (60 percent) say they have a command team in place to maintain information continuity operations from a remote location if a disaster occurs. Close to three quarters of executives (71 percent) discuss disaster policies and procedures at executive-level meetings, and 62 percent have increased their budgets for preventing loss of information availability.”

Source: Harris Interactive

Better prepared? The question is for what? To access information – yes, but not to address human capital, facilities, business operations, etc. – hence a false positive was created.

“Processes and procedures are developed to achieve an objective (usually in support of a strategic objective). Over time goals and objectives change to reflect changes in the market and new opportunities. However, the processes and procedures continue on. Eventually, procedures become a goal in themselves – doing an activity for the sake of the activity rather than what it accomplishes.”

To overcome the effect of “False Positives” and “Activity Traps” the following section offers some thoughts for consideration.

12 steps to get from here to there and temper the impact of all these swans

Michael J. Kami author of the book, ‘Trigger Points: how to make decisions three times faster,’ wrote that an increased rate of knowledge creates increased unpredictability. Stanley Davis and Christopher Meyer, authors of the book ‘Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy,’ cite ‘speed – connectivity – intangibles’ as key driving forces. If we take these points in the context of the black swan as defined by Taleb we see that our increasingly complex systems (globalized economy, etc.) are at risk. Kami outlines 12 steps in his book that provide some useful insight. How you apply them to your enterprise can possibly lead to a greater ability to temper the impact of all these swans.

Step 1: Where Are We? Develop an External Environment Profile

Key focal point: What are the key factors in our external environment and how much can we control them?

Step 2: Where Are We? Develop an Internal Environment Profile

Key focal point: Build detailed snapshots of your business activities as they are at present.

Step 3: Where Are We Going? Develop Assumptions about the Future External Environment

Key focal point: Catalog future influences systematically; know your key challenges and threats.

Step 4: Where Can We Go? Develop a Capabilities Profile

Key focal point: What are our strengths and needs? How are we doing in our key results and activities areas?

Step 5: Where Might We Go? Develop Future Internal Environment Assumptions

Key focal point: Build assumptions, potentials, etc. Do not build predictions or forecasts! Assess what the future business situation might look like.

Step 6: Where Do We Want to Go? Develop Objectives

Key focal point: Create a pyramid of objectives; redefine your business; set functional objectives.

Step 7: What Do We Have to Do? Develop a Gap Analysis Profile

Key focal point: What will be the effect of new external forces? What assumptions can we make about future changes to our environment?

Step 8: What Could We Do? Opportunities and Problems

Key focal point: Act to fill the gaps. Conduct an opportunity-problem feasibility analysis; risk analysis assessment; resource-requirements assessment. Build action program proposals.

Step 9: What Should We Do? Select Strategy and Program Objectives

Key focal point: Classify strategy and program objectives; make explicit commitments; adjust objectives.

Step 10: How Can We Do It? Implementation

Key focal point: Evaluate the impact of new programs.

Step 11: How Are We Doing? Control

Key focal point: Monitor external environment. Analyze fiscal and physical variances. Conduct an overall assessment.

Step 12: Change What’s not Working Revise, Control, Remain Flexible

Key focal point: Revise strategy and program objectives as needed; revise explicit commitments as needed; adjust objectives as needed.

I would add the following comments to Kami’s 12 points and the Davis, Meyer point on speed, connectivity, and intangibles. Understanding the complexity of the event can facilitate the ability of the organization to adapt if it can broaden its strategic approach. Within the context of complexity, touchpoints that are not recognized create potential chaos for an enterprise and for complex systems. Positive and negative feedback systems need to be observed/acted on promptly. The biggest single threat to an enterprise will be staying with a previously successful business model too long and not being able to adapt to the fluidity of situations (i.e., black swans). The failure to recognize weak cause-and-effect linkages, small and isolated changes can have huge impacts. Complexity (ever growing) will make the strategic challenge more urgent for strategists, planners and CEOs.

Taleb offers the following two definitions: The first is for ‘Mediocristan’; a domain dominated by the mediocre, with few extreme successes or failures. In Mediocristan no single observation can meaningfully affect the aggregate. In Mediocristan the present is being described and the future forecasted through heavy reliance on past historical information. There is a heavy dependence on independent probabilities.

The second is for ‘Extremeistan;’ a domain where the total can be conceivably impacted by a single observation. In Extremeistan it is recognized that the most important events by far cannot be predicted; therefore there is less dependence on theory. Extremeistan is focused on conditional probabilities. Rare events must always be unexpected, otherwise they would not occur and they would not be rare.

When faced with the unexpected presence of the unexpected, normality believers (Mediocristanians) will tremble and exacerbate the downfall. Common sense dictates that reliance on the record of the past (history) as a tool to forecast the future is not very useful. You will never be able to capture all the variables that affect decision making. We forget that there is something new in the picture that distorts everything so much that it makes past references useless. Put simply, today we face asymmetric threats (black swans and white swans) that can include the use of surprise in all its operational and strategic dimensions and the introduction of and use of products/services in ways unplanned by your organization and the markets that you serve. Asymmetric threats (not fighting fair) also include the prospect of an opponent designing a strategy that fundamentally alters the market that you operate in.

Summary Points

I will offer the following summary points:

- Clearly defined rules for the world do not exist, therefore computing future risks can only be accomplished if one knows future uncertainty

- Enterprise Risk Management needs to expand to effectively identify and monitor potential threats, hazards, risks, vulnerabilities, contingencies and their consequences

- The biggest single threat to business is staying with a previously successful business model too long and not being able to adapt to the fluidity of the situation

- Current risk management techniques are asking the wrong questions precisely; and we are getting the wrong answers precisely; the result is the creation of false positives

- Risk must be viewed as an interactive combination of elements that are linked, not solely to probability or vulnerability, but to factors that may be seemingly unrelated.

- This requires that you create a risk mosaic that can be viewed and evaluated by disciplines within the organization in order to create a product that is meaningful to the entire organization, not just to specific disciplines with limited or narrow value.

- The resulting convergence assessment allows the organization to categorize risk with greater clarity allowing decision makers to consider multiple risk factors with potential for convergence in the overall decision making process.

- Mitigating (addressing) risk does not necessarily mean that the risk is gone; it means that risk is assessed, quantified, valued, transformed (what does it mean to the organization) and constantly monitored.

Unpredictability is fast becoming our new normal. Addressing unpredictability requires that we change how Enterprise Risk Management programs operate. Rigid forecasts that cannot be changed without reputational damage need to be put in the historical dust bin. Forecasts often times are based on a “static” moment; frozen in time, so to speak. Often times, forecasts are based on a very complex series of events occurring at precise moments. Assumptions on the other hand, depend on situational analysis and the ongoing tweaking via assessment of new information. An assumption can be changed and adjusted as new information becomes available. Assumptions are flexible and less damaging to the reputation of the organization.

Recognize too, that unpredictability can be positive or negative. For example; our increasing rate of knowledge creates increased unpredictability due to the speed at which knowledge can create change.

Conclusion

I started this piece with a question and I will end it with a question. The question is similar to the question at the beginning of this piece.

Question # 2: How much would you have to be paid to accept a 1/2,500 chance of immediate death?

A few minor changes in the phrasing of the questions, changes your perception of the risk and, most probably, your assessment of your value. You will generally place a greater value on what it takes to accept a risk rather than on what you are willing to pay to take a risk. You may recall the wording of the question; if not here it is again:

Question # 1: How much would you be willing to pay to eliminate a 1/2,500 chance of immediate death?

Yet, you pay to take a risk every time you fly! And, on average, you pay $400 – $500 per flight. Daily takeoffs and landings at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago average of 2,409 per day. Daily takeoffs and landings at Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta average of 2,658 per day. This amounts to a lot of people willing to take a substantial risk – taking off and landing safely. The degree of risk is based on the perception of the person regarding their vulnerability to the consequences of the risk that is being posited materializing. Risk is, therefore, never absolute. Risk is set by the receiver of the consequences.

Bio:

Geary Sikich

Entrepreneur, consultant, author and business lecturer

Contact Information:

E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com

Telephone: (219) 922-7718

Geary Sikich is a Principal with Logical Management Systems, Corp., a consulting and executive education firm with a focus on enterprise risk management and issues analysis; the firm’s web site is www.logicalmanagement.com. Geary is also engaged in the development and financing of private placement offerings in the alternative energy sector (biofuels, etc.), multi-media entertainment and advertising technology and food products. Geary developed LMSCARVERtm the “Active Analysis” framework, which directly links key value drivers to operating processes and activities. LMSCARVERtm provides a framework that enables a progressive approach to business planning, scenario planning, performance assessment and goal setting.

Prior to founding Logical Management Systems, Corp. in 1985 Geary held a number of senior operational management positions in a variety of industry sectors. Geary served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army; responsible for the initial concept design and testing of the U.S. Army’s National Training Center and other intelligence related activities. Geary holds a M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance from the University of Texas at El Paso and a B.S. in Criminology from Indiana State University.

Geary is also an Adjunct Professor at Norwich University, where he teaches Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) and contingency planning electives in the MSBC program, including “Value Chain” Continuity, Pandemic Planning and Strategic Risk Management. He is presently active in Executive Education, where he has developed and delivered courses in enterprise risk management, contingency planning, performance management and analytics. Geary is a frequent speaker on business continuity issues business performance management. He is the author of over 200 published articles and four books, his latest being “Protecting Your Business in Pandemic,” published in June 2008 (available on Amazon.com).

Geary is a frequent speaker on high profile continuity issues, having developed and validated over 2,000 plans and conducted over 250 seminars and workshops worldwide for over 100 clients in energy, chemical, transportation, government, healthcare, technology, manufacturing, heavy industry, utilities, legal & insurance, banking & finance, security services, institutions and management advisory specialty firms. Geary consults on a regular basis with companies worldwide on business-continuity and crisis management issues.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Very interesting article. The idea that all models are wrong but some models are useful comes to mind.

With an increasing reliance on mathematical models to manage risk in a wide variety of fields, a thorough understanding of what a model actually represents and what the associated assumptions and limitations are has never been more important.

The failure of the “Value At Risk (VAR)” approach at the beginning of the financial crisis in the last decade painfully highlighted this.

Along with Nassim Taleb’s writing on this subject, I also recommend Douglas W. Hubbard’s books.