The Accuracy Controlled Enterprise: Using Accuracy-Controlled 3T SOPs for Production and Maintenance Quality Assurance

Reliable equipment is necessary to reduce production costs and maximise production throughput. High reliability from operating equipment requires high quality reassembly, coupled with the correct operating practices. You can guarantee correct maintenance and proper plant operation by specifying a target and tolerance in maintenance and operating procedures.

Having a target and tolerance sets the recognised acceptance criterion. A simple proof-test will confirm if it has been met. Specifying a mark and tolerance range changes the focus from one of simply doing the job; to now doing the job accurately. This results in high quality trades’ workmanship and sound equipment operator practices that deliver reliable equipment performance. Those organisations that use ‘target, tolerance, proof-test’ methodology in their procedural tasks move from being a quality-conscious operation to being an Accuracy-Controlled Enterprise (ACE).

Keywords: standard operating procedure, SOP, accuracy-controlled enterprise, work quality assurance

Abstract

Do you know that your workforce can prevent nearly all plant and equipment breakdowns! If your maintenance people do their work accurately to design specification, and your operators run the equipment precisely as intended, they can make the equipment work so well that it becomes superbly reliable.

There is no need to be doing repairs sooner than required by the design if the equipment is rebuilt accurately and run correctly Accuracy is defined as “the degree of conformity of a measured or calculated value to its actual or specified value.” To have accuracy you need a target value and a tolerance of what is acceptably close to the target to be called accurate.

How many defects, errors and failures can your operation afford to have each day? Does your maintenance crew have the time to go back and do a job twice or three times because it was done wrong the first time? Are people happy to regularly accept wasted production and lost time due to stopped equipment? If not, then do your internal work procedures support doing the job right the first time?

Exceptionally reliable production equipment running at 100% design capacity should be normal and natural. Your plant and equipment were designed to work reliably. The maintenance was intended to sustain the design reliability. Its operation should be as the designer anticipated. The designer wanted reliable 100%-rate production.

If under operation you are not getting the reliability designed into the equipment, then something is amiss. The challenge becomes to identify what is preventing the equipment from delivering the performance it was designed to give.

Very occasionally the fault lies with the design itself. Typically, the wrong material was selected for the job. Either it was not strong enough for the stresses induced in it or it was incompatible with materials contacting it. Once a design problem is identified the necessary change is made to enable the equipment reliability to rise to the design intent.

Much more often the reason equipment does not meet its designed reliability is because it is installed wrongly, it is built or rebuilt poorly, and it is operated not as designed. Usually this happens because people involved in its installation, care and running do not know the right ways.

Though most operators and maintainers have some recognised training it can never be enough to competently handle all situations. In those situations where they have not been trained, they are forced to use what knowledge they do know to make a decision. If it is the wrong choice and no one corrects them, it becomes the way they solve that problem again in future.

The Start of Defects, Failures and Errors in Your Business

Unfortunately, many decisions of this type do not have an immediate bad impact. If they did, it would be good, because the worker would instantly self-correct and get it right. No, most errors of choice or ignorance do not impact until well into the future. The chosen action was taken and nothing bad occurred. Which meant the operator or tradesman thought it was the right decision, since things still ran fine. That is how bad practices become set-in-place in your operation.

There is nothing wrong with making a wrong decision. Provided it is corrected immediately and nothing bad happens, there was no harm done. Bad things happen when bad decisions are allowed to progress through time to their natural and final sad conclusion. Regrettably, there are very few decisions that will give you instant replay options.

If it is important in your company to have low maintenance cost and exceptionally reliable production equipment, then your internal work systems must support that outcome. All work done by operators, maintainers, engineers, and managers need to go right the first time.

Why We Have Standard Operating Procedures

Companies have long recognised that if you want consistent, reproducible, correct results from your workforce they need to work to a proven and endorsed procedure. The procedure provides clear guidance, sets the required standard, and stops variations in work performance.

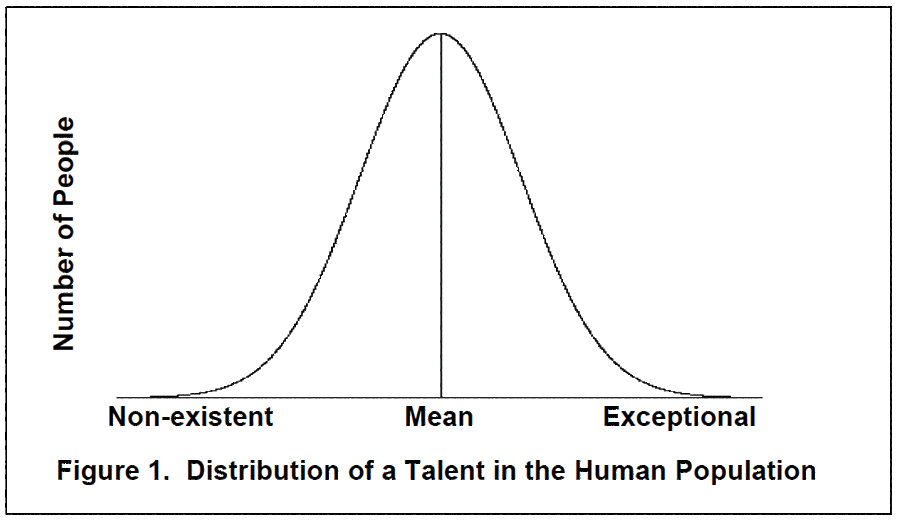

Variations in work performance arise because human skills, talents and abilities are typically normally distributed. If we were to gauge the abilities of a wide cross-section of humanity to do a task, we would end up with a normal distribution bell curve. Secondary and tertiary learning institutions understand student results follow a normal distribution curve. A normal Gaussian distribution bell curve of a talent in a large human population is shown in Figure 1.

The implication of such a distribution is that for most human skills and talents there are a few exceptionally able people, a few with astoundingly poor ability and lots of people in-between clustered around the middle or mean.

If your workplace requires highly able people to make your products and do your maintenance, then from the distribution curve of human talent you are going to find it hard to get many people who are that good. The ones you do get will cost you a lot of money because they are the elite in the industry. Hence standard operating procedures were created to use people from the around the middle and below ability levels to do higher standard work than they naturally could do unassisted.

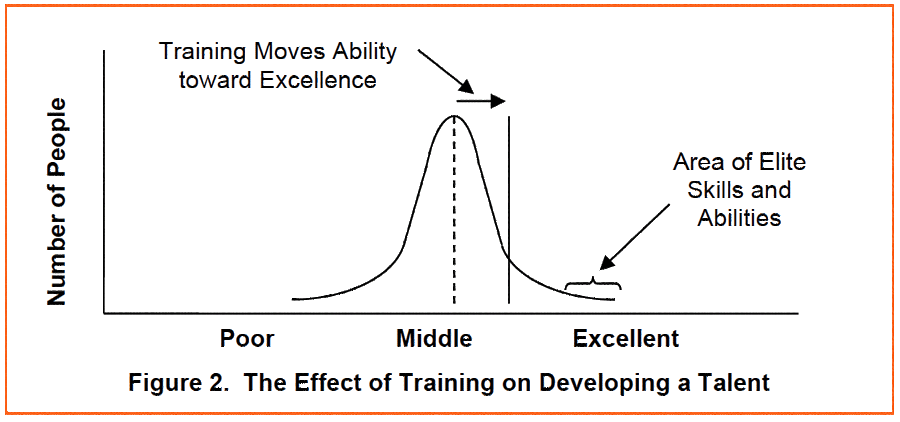

The talent distribution curve also explains why the continual training of your people is so important to your company’s long-term success. If the available labour pool is clustered around the mean performance level of a skill, then a good way to improve the population’s ability to do the skill is to teach them how to do it better. Training has the effect of moving average performers toward the elite portion of the population. This is shown in Figure 2.

The Cost of Poorly Written Standard Operating Procedures

Since standard operating procedures (SOPs) control the quality of the work performed by people not expert in a task, they are clearly critical to the proper running of a business. It is also critically important

that they are written in ways to promote maximum efficiency (make use of the least resources) and effectiveness (done in the fastest correct way).

It has been my experience that very few companies use their SOPs to control outcomes. When they are available, they are not self-checking and do not promote good practice. They offer little practical assistance to the user. Typically, they are glanced over when operators and maintainers start a new job and then thrown to the back of the shelf to never be seen again. That is a pity because they are one of the most powerful learning tools ever developed. At least they could be if their supervisors and managers knew what could be done with an SOP.

Of the companies that have SOPs, most were written by their resident expert in the job. They wrote the procedure already knowing all the answers. So, tasks were described with words and statements that assumed prior knowledge. You will often see in SOPs statements such as – “Inspect lights, check switch, check fuse, and test circuit”. And “Inspect steering wheel linkage”. Or in the case of a machine operator – “Test the vehicle and report its condition”.

The problem with the use of procedures containing such descriptions is that you must first be an expert to know whether there is anything wrong with what you are looking at. They require you to hire trained and qualified people to do what is maybe a quite simple job.

The Best SOPs Can Be Done by The Least Skilled People.

There is a better way to write SOPs that still maintain the work quality but do not need only qualified people to do them. They can be written with more detail and guidance and include a target to hit, a tolerance on accuracy and regular proof-tests of compliance so that job quality is guaranteed.

Standard operating procedures are a quality and accuracy control device which has the power to deliver a specific level of excellence every time they are used. Few companies understand the true power of an SOP. Typically, they are written because the company’s quality system demands it. People mistakenly write them as fast as they can, with the least details and content necessary.

SOPs should be written to save organisations time, money, people, and effort because they can make plant and equipment outstandingly reliable so production can maximise productivity!

For a standard operating procedure to have positively powerful effects on a company and its people there must be clear and precise measures, which if faithfully met, will produce the required quality to deliver the designed equipment performance. Great production plant reliability and production performance will naturally follow!

If we take the “Inspect steering wheel linkage” example from above and apply the ‘target, tolerance, proof’ method, a resulting description might be:

“With a sharp, pointed scribe mark a straight line directly in-line on both shafts of the linkage as shown in the accompanying drawing/photo (A drawing or photo would be provided. If necessary, you also describe how to mark a straight scribe mark in-line on both shafts). Grab both sides of the steering linkage and firmly twist in opposite directions. Observe the scribe marks as you twist. If they go out of alignment more than the thickness of the scribe mark replace the linkage (a sketch would be included showing when the movement is out of tolerance).” The procedure would then continue to list and specify any other necessary tests and resulting repairs.

With such detail you no longer need a highly qualified person to do the inspection. Anyone with mechanical aptitude can do a reliable inspection. This method of writing procedures is the same as used by writers of motor car manuals for novice car mechanics. Car manuals are full of procedures containing highly detailed descriptions and plentiful descriptive images. With them in-hand novice car mechanics can do a lot of their own maintenance with certainty of job quality.

The very same logic and method used to write car manuals also applies to industrial production and maintenance procedures. If you put in your procedures all the information that is necessary to rebuild an item of equipment, or to run a piece of plant accurately, you do not need people from the exceptional end of the population to do the job well.

Train and Retrain Your People to Your Standard Operating Procedures

Having a procedure full of best content and excellent explanations for your workforce is not by itself enough to guarantee accuracy. How can you be sure that your people comprehend what they read? Many tradesmen and plant operators are not literate in English, nor do they understand the true meaning of all the terms used in a procedure.

To be sure your people know what to do and can do it right, they need to be trained in the procedure and be tested. Training is needed before they do the task alone, without supervision, and later they need refresher and reinforcement training. The amount and extent of training varies depending on the frequency a procedure is done, the skill level of the persons involved and their past practical experience in successfully doing the work.

Procedures done annually or more often by the same people will not need retraining. Because people forget, those procedures on longer cycles than annually will need refreshment training before they are next done.

Training and retraining often seems such an unnecessary impost on an organisation. You will hear managers say “If the work is done by qualified people why do I need to train them? They have already been trained.” The answer to that question is “How many mistakes are you willing to accept?”

For example, if you have had flange leaks soon after a piece of equipment was rebuilt, it is a sign that you may need to retrain you people in the correct bolting of flanges. Flanges do not leak if they were done right. When a repair re-occurs too often, it is a signal that the SOP does not contain targets, tolerances, and proof-tests or that training is needed to teach people the procedure.

Taking Your Organisation to an Accuracy Controlled Enterprise

A classic example of what great value an accuracy-focused SOP can bring is in this story of a forced draft fan bearing failure. The rear roller bearing on this fan never lasted more than about two months after a repair. The downtime was an expensive and great inconvenience. To take it out of the realm of a breakdown, the bearing was replaced every six weeks as planned maintenance.

The bearing was also put on vibration analysis condition monitoring observation. After several replacements enough vibration data was collected to diagnose a pinched outer bearing race. The rear bearing housing had been machined oval in shape when manufactured and it squeezed the new bearing out-of-round every time it was bolted up.

You could say that vibration analysis was applied wonderfully well. But the truth is the repair procedure failed badly. If there had been a task in the procedure to measure the bolted bearing housing roundness and compare the dimensions to allowable target measurements, it would have been instantly noticed as having an oval shaped hole at the first rebuild.

There was no need for the bearing to fail after the first time! A badly written procedure had let bad things happen! Whereas an accuracy-controlled procedure with targets, tolerances and proof-tests would have found the problem on the first repair and it would have been fixed permanently.

You can convert existing quality procedures to accuracy-controlled operating procedures with little development cost. The only extra requirement is that you include a target with tolerances and a proof-test in each procedural task to give feedback and confirmation the task is done right. The partial example at the end of the paper shows how it is done.

The problem with targets is that they are not easy to hit dead-centre. It is not humanly possible to be exact. If a procedural task states an exact result must be achieved, then it has asked for an unrealistic and virtually impossible outcome. A target must be accompanied with a tolerance range within which a result is acceptable. There must be upper and lower limits on the required result.

Even the bullseye in an archery target is not a dot; it is a circle with a sizable diameter. You can see the bullseye in Figure 3 is not a pin prick in size. Anywhere within the bullseye gets highest marks. So must be the target for each task in an accuracy-controlled procedure.

A professionally written accuracy-controlled procedure contains clear individual tasks; each task has a measurable result observable by the user and a range within which the result is acceptable. If you do this to your procedures, you build-in accuracy control. With each new task only allowed to start once the previous one is within target; you can guarantee a top-quality result if the procedure is followed as written.

With targets set in the procedure, its user is obliged to perform the work so that they hit the required target. Having a target and tolerance forces the user to become significantly more accurate than without them. When all the task targets are hit accurately, you know the procedure was done accurately!

Once a procedure always delivers its intended purpose you have developed a failure control system. No longer will unexpected events happen with work performed accurately to the procedure.

Conclusion

Procedures need in-built accuracy to prevent failure and stop the introduction of defects. To ensure each task is correctly completed the worker is given a measurable target and tolerance to work to. The procedure is done correctly when its individual tasks are all done to within their target limits. Using this methodology in standard operation procedures makes them quality control and training documents of outstandingly high value and accuracy.

The organisations that use sound failure control and defect prevention systems based on proof-tested, accurate work, move from being a quality conscious organisation to being an accuracy-controlled enterprise, an ACE organisation.

With that level of accuracy in maintenance, operation, and engineering tasks you will naturally get outstanding equipment reliability and consistently high production performance.

All the best bests to you,

Mike Sondalini

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply