I have often heard employees complain they have no data to initiate a proper Reliability Improvement Program. This is not always true. And to no fault of theirs. They just don’t know how to use what they already have in terms of records. If you are running an operation, you should at least have production records – i.e. how much you are producing on a daily basis. If you don’t have this, then maybe you should not be in business at all. This article looks at ways to initiate a Reliability Program using the Barringer Process Reliability (BPR) methodology. The greatest advantage of this methodology is that it only requires productions records as an input. That is how many units of production the plant produces on a daily basis. For example, the barrels of crude oil processed per day in a refinery. Or the hectoliters of beer brewed in a brewery daily.

Barringer Process Reliability

BPR was developed by Paul H. Barringer, a fellow reliability engineer “extraordinaire” and an outstanding mentor for myself and countless others in this field of practice. BPR highlights operational issues. Not addressed and mitigated, those could have significant revenue impacts for the company. A BPR analysis uses the Weibull probability plot which happens to be a very well-known tool in the field of Reliability Engineering. On one side of a sheet of paper only, the BPR plot can tell the true “story” of the operation.

The Weibull technique and BPR graphics provide important information useful to a plant operator attempting to quantify production losses and/or seeking to solve business problems. One-page summaries, as opposed to long reports, are very important for busy people, particularly senior leaders. Managers always look down on the process from a “10,000-foot” level, and what they see matters differently than the field worker who is at the “1-foot” level. By nature of their job and no fault to them, field workers always see the process from a low altitude where the view can be overwhelming due to a maze of problems.

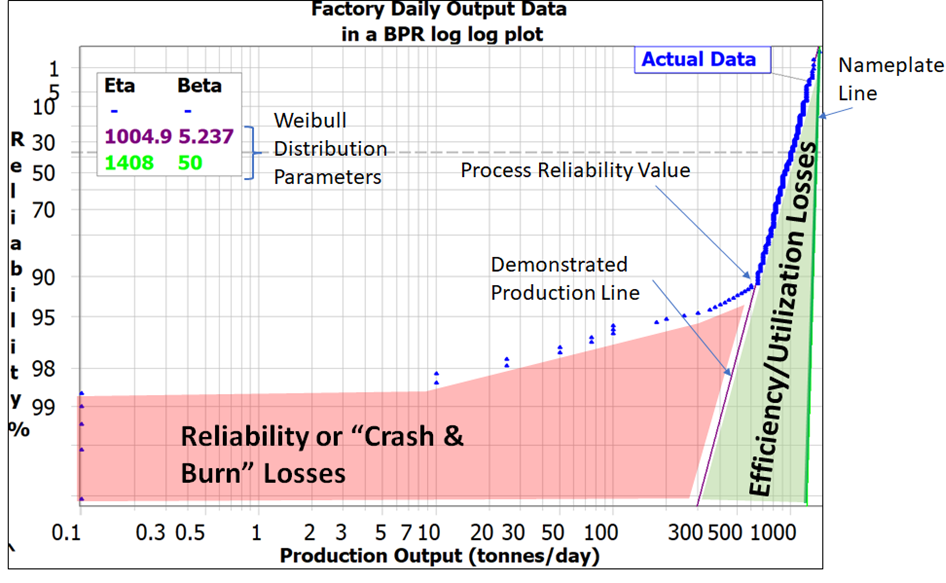

Graph 1 below provides and example of a BPR plot for an ore factory. As mentioned above, it is the “story” of the operation on one “single sheet of paper”. Or the 10,000-foot bird’s eye view.

Using Barringer Process Reliability to initiate a Reliability Program

As shown above, a BPR plot can provide an organization with the following information:

- Production Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

- Production loss quantification as a result of poor “factory” performance.

- How much control operators have on the process.

In Graph 1, the BPR plot highlights two specific areas where one can start improving the performance of the plant.

- The Reliability or Crash and Burn Losses: these are the obvious high impact events that cause major losses to the system. Examples are power outages, unplanned shutdowns or critical equipment failures. Since they are rather obvious events, it is relatively easy to investigate their cause(s).

- The Efficiency and Utilization Losses: they relate to more subtle issues that require in depth knowledge of the system or process. Those losses are mostly related to wastage or late starts. They also stem from physical stresses on the plant assets relating to physico-chemical conditions such as temperatures, pressures, flow rates, as well as chemical concentrations.

According to Paul Barringer, Reliability or Crash and Burn losses can be tackled using the Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Process. Whereas the Efficiency and Utilization losses are best addressed by the Six Sigma improvement method.

The above paragraphs highlight that a Reliability Program can be initiated with only production records. There is no need to source complex equipment records. Therefore, “No Data equals no Reliability Program” is a false concept! You actually have more data than you think!

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Thanks Andre-Michel for pointing out that factory data can be used. I used Paul Barringer’s and Kececioglu’s Weibull parameter estimates when I couldn’t get field reliability data. https://profitabilityllc.com/paul-barringer-legacy/

Companies are required by GAAP to have revenue and cost data that can be used to derive ships and returns counts by accounting period, for products, and bills of materials to derive ships and returns counts for service or spare parts. Some work required.

I try to help.

Thanks for the reading my article Larry. and thanks to pointing out Kececioglu’s work. Interesting read!