Generally speaking, pushing value through functional silos usually creates inefficiencies, low buy-in, and a lack of ownership. Resistance to change is almost guaranteed, not to mention the problems caused by missed or poor communication. The same applies to reliability engineering activities during product or process development, which often face strong resistance from design teams, to say the least.

In my 12 years of reliability experience, I’ve seen that reliability engineering is often viewed as just another function — another group asking designers to do extra work because their “baby” (design) is “ugly.” This mindset exists largely because traditional engineering education focuses more on how things function given the boundary conditions, not how they degrade, specifically, how they degrade over time. Let me explain.

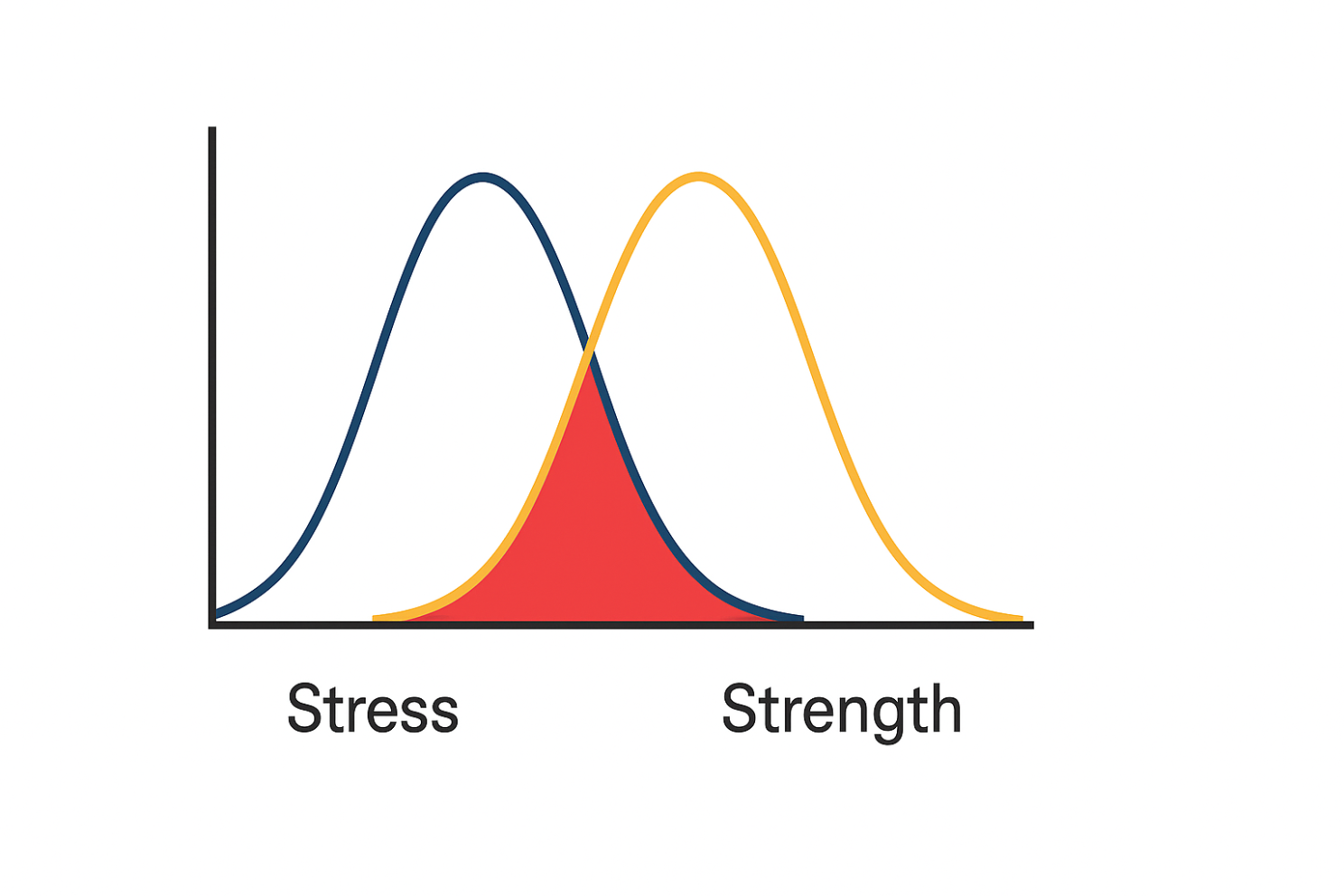

The current engineering education system, specifically at the Bachelor level, focuses primarily on deterministic approaches, with minimal consideration for uncertainty and/or variability. Boundary conditions are known (loads, environmental stresses), use profiles are known, products are built with no defects, and material properties are fixed values. This is an engineering hope that is rarely true. All these combined create a perception of a discrete, fixed product life expectation.

The easy solution that has been the main “medication” in engineering is adding safety margins. However, if variabilities are not well understood, even this approach won’t save your product from failing unexpectedly—not to mention the side effects of this “medication,” such as increased cost, weight, etc.

Now imagine a scenario where a reliability engineer tells the product design engineer that his life estimation is not realistic, his testing approach does not guarantee the expected life, and so on. I think it is not difficult to imagine this situation as I described it above, similar to telling someone that “your baby is ugly.” This creates a tense situation between design and reliability engineers, although reliability should be an important part of product design.

So, how do you solve this problem? In my opinion, the most effective solution is to make design engineers also reliability engineers. Reliability is not an outside function to help product design; it should be at the core of it. When you design something to function, you also need to think about how to keep it functioning.

When you design something to function, you also need to think about how to keep it functioning.

It was a big surprise to me in the early years of my career every time I heard from design engineers that they basically didn’t know how their product might fail. They did not know what to test in life testing. Over the years, I realized that this is common across many industries, and I think this creates waste in terms of time, money, and brand reputation.

When design engineers don’t understand that time to failure is a random process affected by many factors, such as variabilities in design itself, the environment it is exposed to, manufacturing, usage, etc., they generally don’t understand why they need to conduct failure tests and why more samples need to be tested. They don’t understand why success-based life testing with only 1–2 samples does not guarantee life for 100, 100,000, or sometimes millions of products they are going to build. They don’t understand why getting failures is a blessing, not a disaster.

I personally heard many times during my conversations with product design engineers: “I design to pass, not to fail.” This needs a paradigm change, since failures are seen as undesired, bad events, even during test processes.

I often explain this challenge with a simple analogy. Imagine trying to estimate the average life expectancy of an entire city or country by looking at just one person who is still alive. That tells you nothing useful about the expected lifespan. Even if you expand the sample to a few individuals, without data on mortality (failure time) you still lack the statistical confidence needed to draw reliable conclusions. With a statistically significant sample size and no failure data (success-based), you can argue how long a product may survive without failure, but you cannot say with confidence when it will fail. These two things are different, and usually the latter is more important. You need to get failure data.

I could have kept this section short, but this is my observation over a decade, and you would be surprised – this is still the case in many companies. I know design engineers will also read this article, and I want them to understand what the problem is and how it affects product success.

In summary, all these are reliability engineers’ concerns and an uphill battle that slows progress and kills motivation. So when I said we don’t need reliability engineers, I didn’t mean that reliability engineering doesn’t matter. What I meant was that reliability is a value, just like quality or safety, and it should be the responsibility of everyone involved in development.

Perhaps we don’t even need separate reliability engineering roles, as that responsibility could be carried by design engineers themselves. Adding another layer often creates problems with communication and ownership. An extra communication layer dilutes value just as adding another component would degrade a system’s reliability.

It’s similar to how, in some companies, design engineers also act as systems engineers: they define requirements, they own them, and they’re responsible for them. Systems engineering still exists, they generally own the processes, but many systems engineering activities are integrated into design engineering.

Generally, a company is known for its product reliability when reliability is in their culture. In every decision they make about products, they consider reliability. That applies to supply chain, storage, transportation, and design process.

Over the years I developed a sense for recognizing a reliability-oriented company culture. You see it when design engineers talk about FMEAs as a risk reduction tool and use findings to improve the product. You see it when design engineers talk about test-to-failure, sample size, Weibull distribution modeling, etc.

And believe me, this is not a distant hope – there are so many companies out there who were able to build this culture. Why shouldn’t yours be the next?

I hope you enjoyed the content and that it offered some useful takeaways. Engaging with this post by commenting, or sharing helps it reach others who may benefit as well. Please follow me on Linkedin.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply