Newton’s 3rd Law and Systems Thinking are two of the most important concepts every engineer needs to understand deeply. I hear you saying, “Come on, Ayaz, which engineer does not know about Newton’s 3rd Law?”

My response? Quite a lot.

I am not talking about memorizing the formula and applying it in a calculation. I am talking about truly understanding its philosophy. It is a philosophy that explains the nature of interrelated, complex systems. There is no absolute win in this world. We live in a complex reality where everything, literally everything, is connected.

Do you remember the concept of the Butterfly Effect? It is the idea that a small change in one place, like a butterfly flapping its wings in the Savanna, can eventually cause a tornado somewhere else. It illustrates that a change in one part of a system inevitably causes a change in another part. Good engineering is to be aware of these impacts and manage them.

Engineering works the same way. You push on one parameter, and another one reacts.

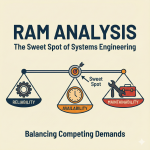

In the world of reliability and maintainability, we have a concept called RAM (Reliability, Availability, and Maintainability) analysis. It fits perfectly into the systems thinking mindset because it forces us to find a reasonable balance between competing demands.

What you will get out of this article

RAM analysis is a staple in complex system analysis. It looks for a balance between 3 critical parameters: Availability, Reliability, and Maintainability. By the end of this article, you will have a clear understanding of these parameters and how to balance them in product or process design.

As always, this was one of the topics I struggled to grasp in the early years of my career. My goal is to make it crystal clear for you in the next few minutes.

Definitions

Let’s define our terms first so we can build on a solid foundation. There are various formal definitions out there, but I am going to share the common, practical ones that are not tied to a specific regulatory body.

Availability

The probability that a product is in a state to perform its designated function(s) under stated environmental and use conditions at a given time.

In simplest terms: Is your product or process ready to run safely and perform as required whenever it is demanded?

For instance, an airline’s business case relies heavily on availability. If there is demand for a flight, that airplane must be ready to go. If it is sitting in a hangar, it is not making money.

Reliability

The probability of a product performing its intended function(s) under stated environmental and use conditions without failure for a given period of time.

I believe this section does not need a detailed explanation since I talk about this topic in almost every article. If you are new here, I highly recommend reading my “Reliability Engineering 101” and “Design for Reliability Process” articles first.

Maintainability

The probability that a given maintenance action can be performed within a stated time interval, using stated procedures and resources.

An easy example is the difficulty of repairing your own car. You have probably heard friends say, “It is a pain in the neck to replace a water pump or a filter on this car.” German cars are specifically known for poor maintainability. I won’t name names, but BMW is my favorite example here. 😉

When a system is designed with poor maintainability, it takes highly skilled technicians and special tools hours to fix a simple issue. When it has good maintainability, the system is designed to be fixed quickly, easily, and safely. Maintainability is an interesting design feature and deserves an article to go deeper. I will work on this.

Maintainability is also the one people usually get wrong. Maintainability is NOT maintenance. They are two different things, though obviously related.

Think of it this way: Maintainability is a design feature. Maintenance is the action in operation. Your maintenance success depends on your reliability and maintainability.

One thing I really want to point out here is that all three of these parameters are probabilistic. They are not single numbers; they are distributions that need to be modeled.

The Sweet Spot: Finding the Balance

As I mentioned at the beginning, we need a systems approach to balance RAM because these parameters impact each other.

Availability usually comes directly from the business case or operational goals. A product (like a robotaxi) or a process (like a chemical plant) needs to be available to generate revenue. Every second, minute, or day the asset is out of operation, whether due to failure or scheduled maintenance, the company loses money.

You will typically hear a requirement like: “My product must be 95% available annually to fulfill the business case.”

The question then becomes: How do we achieve that availability?

Mathematically, availability is a function of Reliability and Maintainability, which is best explained with our famous “RAM Bermuda Triangle.”

To improve Availability, you either need to fail less (High Reliability) or fix it faster (High Maintainability).

Depending on your constraints, there are 3 potential scenarios design teams may face. Let’s break them down.

Scenario 1: Only an Availability Requirement Exists

This is quite possible, and I have seen it often in my career. This is the most flexible scenario for a design team. Since the business only cares that the machine is running (Availability), the engineering team can trade reliability against maintainability, or vice versa.

Pros

- Simple requirement to communicate.

- High design flexibility. You can use cheaper, less reliable parts if you make them incredibly easy to swap out.

Cons

- Risk of high operational costs (OpEx). If you lean too heavily on Maintainability, you might have a machine that breaks every day but takes 5 minutes to fix. It might meet the Availability target, but the logistics and spare parts costs will be a nightmare.

- The Flip Side: If you lean too heavily on Reliability, you might have a machine that rarely breaks, but when it does, it requires weeks of downtime, special tools, and highly specialized technicians to fix.

Scenario 2: Availability and Reliability Requirements Exist

In this scenario, the business dictates two sides of the triangle: “The machine must be available 95% of the time, AND it must run with 95% reliability over the mission duration.”

This is the most common scenario because customers view frequent failures as a sign of a poor quality, even if repairs are fast. Additionally, most purchasing contracts explicitly demand a guaranteed failure free interval alongside availability to ensure operational stability.

There are also cases where maintainability is not a consideration at all because maintenance is impossible (e.g., satellites, at least for now, in-space structures, etc.). This fact alone explains the high cost of these structures, because availability rests solely on the shoulders of Reliability, which is not cheap to achieve.

In this scenario, Maintainability becomes a mathematical constraint. You no longer have a choice. If Availability is fixed and Reliability is fixed, you must achieve a specific restoration time to make the math work.

Pros

- Ensures the product is not failing constantly (protects brand reputation).

- More predictable spare parts consumption.

Cons

- It forces the design team’s hand. If the calculated maintainability target is too aggressive (e.g., “Must be repaired in 10 minutes”), it might drive up the design cost (CapEx) significantly to add modularity and fault detection capabilities.

Scenario 3: Availability and Maintainability Requirements Exist

This is generally not a desired scenario and is less common, but there are specific cases where it makes sense. In this scenario, the user focus is not on how often it breaks, as long as the system is up most of the time and fixes are quick.

When does this make sense? (The Pros)

- Consumables: Some parts are designed to wear out (tires, cutting blades, filters). The customer knows failure is inevitable. They care that the machine is running (Availability) and that swapping the blade takes 2 minutes (Maintainability).

- High Stress Operational Tempo: Think of a Formula 1 pit stop or a military vehicle in a combat zone. Things will break. The priority shifts from “Make a tank that never breaks” (expensive) to “Make a tank the crew can fix in the field in 15 minutes.” The constraint is the repair window, not the failure interval.

- Low Skill Workforce: If the end user has high turnover or low technical skills, the business might prioritize Maintainability (“Plug and Play” modules) over Reliability. They would rather have a cheaper machine that breaks more often but is “idiot proof” to fix.

- Safety Critical “Time to Recovery”: In some safety systems, the duration of the failure is more dangerous than the frequency (e.g., mine ventilation). The requirement becomes: “If it stops, it must be back on in 5 minutes.”

Cons

- The Hidden Trap: Since you are not constrained by a specific failure rate, you might be tempted to use cheap, low reliability components. You end up with a machine that meets the requirements but breaks constantly, leading to operator fatigue and frustration.

- Supply Chain Vulnerability: There is also a major risk regarding supply chain vulnerability. Since this strategy relies on swapping parts frequently, any delay in the spare parts supply chain will immediately destroy your availability.

Independence: A Critical Note

I also want to point out that Reliability and Maintainability might seem completely independent, but they are not.

Maintainability directly impacts operational reliability. If a system is difficult to repair, inspect, or replace, the maintenance action itself can induce new damages. We call this “maintenance induced failure.” If you make it hard to fix, the technician might break something else while trying to fix the original problem.

We usually say the best maintenance strategy is when we don’t have to touch the equipment at all.

In Summary

Engineering is all about working under various constraints and finding a balance that is economically and technically feasible. RAM engineering is no different.

You might be tempted to ask, “Why not just maximize all three? Why not have zero failures, instant repairs, and 100% availability?”

The answer the question below:

- Exponential Cost: To squeeze out that last 0.01% of reliability, you need exotic materials and extreme redundancy, making the product too expensive to sell.

- Time to Market: Designing a “perfect” system takes years. By the time you launch, your competitors will have already captured the market with a “good enough” product.

- Complexity & Weight: To make something instantly repairable and perfectly reliable, you often add complex sensors and mechanisms. Ironically, this added complexity often creates new failure modes!

The true skill of a reliability engineer is not maximizing every parameter, but finding the specific balance that delivers safe and effective performance at a price the market can accept

I hope you enjoyed the content and that it offered some useful takeaways. Engaging with this post by commenting, or sharing helps it reach others who may benefit as well. Please follow me on Linkedin.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Excellent article indeed on the power and versatility of RAM analysis. Thank you for sharing your insightful thought on this subject. May I add just one aspect.. adding redundant equipment to improve availability. Comes at a cost obviously and needs to be carefully evaluated.

Thank you Andre-Michel. Thanks for the comment. Do you think adding redundancy will increase reliability but it may have negative impact on maintainability? Such as congested area, complexity of isolation, etc.