In an increasingly complex and interconnected world, ensuring that systems—from machinery to software, from power networks to consumer products—perform reliably across their intended lifetimes, is essential not only for safety and quality but also for economic viability. This intersection between ensuring dependable performance and managing costs is broadly studied under what is known as Reliability Engineering and Economics. Or Relia-nomics.

Economics and Reliability in Industry

The study of economics is a social science primarily concerned with analyzing the choices that individuals, businesses, governments, and nations make to allocate limited resources. This discipline studies how societies manage scarce resources to produce, distribute, and consume goods and services.

Reliability engineering is a sub-discipline of systems engineering focused on the ability of a product, system, or service to perform its intended function under specified conditions for a defined period of time. In simpler terms: reliability is the probability that something will not fail when you expect it to work.

Both specialities come together in industrial settings. The reason is obvious. For the most part though not always, those settings are for profit. Shareholders, salaries and other expenses are due. Capital investments require funding. Financial resources are finite, leading to prioritized spend. Reliability and Economics must come together because reliability decisions are only “good” when they optimize risk and value, not just technical performance. Engineering models (failure modes, probabilities, consequences, maintainability, spares, downtime exposure) quantify what can go wrong and how often; Economics translates that into comparable business terms (total cost of ownership, cost of unreliability, lifecycle cash flows, and risk-adjusted trade-offs). When these disciplines are integrated, organizations can justify the right interventions. Whether that is redesign, preventive maintenance, condition monitoring, redundancy, inventory strategy, or run-to-failure, based on the marginal return per dollar and the acceptable level of operational, safety, and environmental risk. The result is decision-making that prioritizes the highest-value reliability improvements, avoids over-engineering and under-maintenance, and aligns plant performance with financial outcomes and governance expectations.

Practical Example

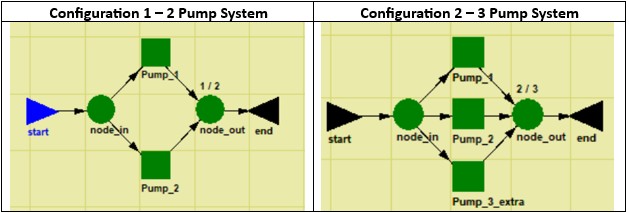

In the example below, we look at the Life Cycle Cost of a simple production system comprised of 2 pumps. We are at the design stage where all the calculation are “on paper” so to speak. It is a critical stage where configurations are evaluated methodically but at minimal cost (i.e. on paper), before being implemented in the field. Post commissioning and field modifications can be very expensive.

The pumps combined are required to produce a specific output of 400 m3/hr. This output translates into revenue which is the first operational measure of economics. On the other hand, the operation of a pump also comes at a cost including the following:

- Purchase or capital cost (each pump costs $1 million to install)

- Maintenance Cost (Repair, preventive maintenance, spares)

- Operating costs (e.g. utilities)

Life analysis estimations are required. They relate to the failure and repair statistical distributions. From an operational standpoint, each pump can provide a maximum output of 200 m3/hr. As mentioned above, the system is required to push out a total of 400m3/hr. This is a pretty “tight” operation. Each pump is required to perform continuously. And at its maximum capacity.

Reliability relates directly to system or component failures. In other words, the system and its subcomponent will fail and impact revenue. In order to improve reliability and subsequently economics, the question to be asked is: is a 2-pump configuration design more “economical” or should the design consider a 3-pump configuration?

Both configurations are highlighted in Diagram 1 below.

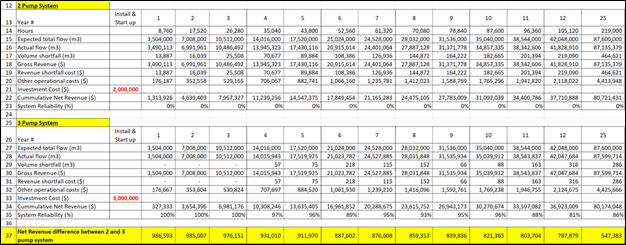

Using a Reliability, Availability and Maintainability (RAM) model, one can estimate the net revenue related to both configurations over time. The result is provided in Table 1 below. The inputs related to the model programing are provided in a spreadsheet (link here) should the user wish to replicate this exercise.

The objective is to obtain the maximum net revenue from each of the 2 configurations. Based on the results in Table 1, the 2-pump configuration is the best choice since the net revenue is highest for each year. That is comparing Row 22 and Row 34 in Table 1 below.

Pure economists or accountants will denounce the missing elements in this Life Cycle Analysis. Where is the time value of money? Where is the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) or the Net Present Value (NPV) calculations? And they are absolutely correct. However, this is when Reliability and Economics come together. Reliability engineers and accountants regroup as a team to refine the Life Cycle Costs. It becomes true teamwork and effective decision making.

It is interesting to note in Table 1, that the reliability for a 2-pump system is always zero (Row 23) even though this configuration is the most economical choice. Reliability is zero because the system has failed at least once during its required mission time. Comparing rows 23 and 35, it appears that reliability would have been “sacrificed” for economics. The reality behind all this is that an extra million-dollar investment does not necessarily pay off. In this comparative example, dealing with low or zero reliability is a more economical choice. Provided of course that recurring failures don’t introduce other risks such as personal safety or asset integrity.

Conclusion

Reliability engineering remains essential to ensure systems perform as intended over time. But without the lens of economics — lifecycle cost analysis, cost-benefit evaluation, risk trade-offs — it’s hard to justify how much reliability is “enough.”

Relia-nomics bridges that gap: it helps engineers, managers, and decision-makers evaluate the economic value of reliability — minimizing total cost across design, operation, maintenance, and failure.

As systems grow more complex and stakes higher, adopting a rigorous, economically informed reliability mindset — a kind of engineering “Relia-nomics” — becomes not just desirable, but essential for sustainability, performance, and long-term value.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Thank you Andre Michel . very good article with use case of LCC of Pump. indeed, Life Cycle Costing (LCC) is a cornerstone of effective reliability and asset management because it enable the decision-making from short-term cost to long-term value.

Thanks for the feedback Yousuf. As mentioned in the article, The LCC analysis is a good bridge to engage accountants and financial professionals in the organization. Happy holidays!