As many of you know, I have been encouraging my LI contacts for years to take me up on my offer to review any pictures they have of failed parts, and we would try and provide them some preliminary feedback. Well, someone finally took us op on the offer and we wanted to share what was learned (we obtained permission to do so providing the company name was not used).

Here was the original inquiry via LI instant messenger along with the pictures:

“Dear Sir, As per your advise, I’m sending you a photo of failed flange bolts. I belief they were failed due to fatigue. Could you please review them and identify/ label their failure mode. After your comments on this photo, I’ll put up a recommendation on my RCA. Looking forward to hear from you. Regards.”

I passed these pics to three (3) of my experts who do this for a living and got back the following responses:

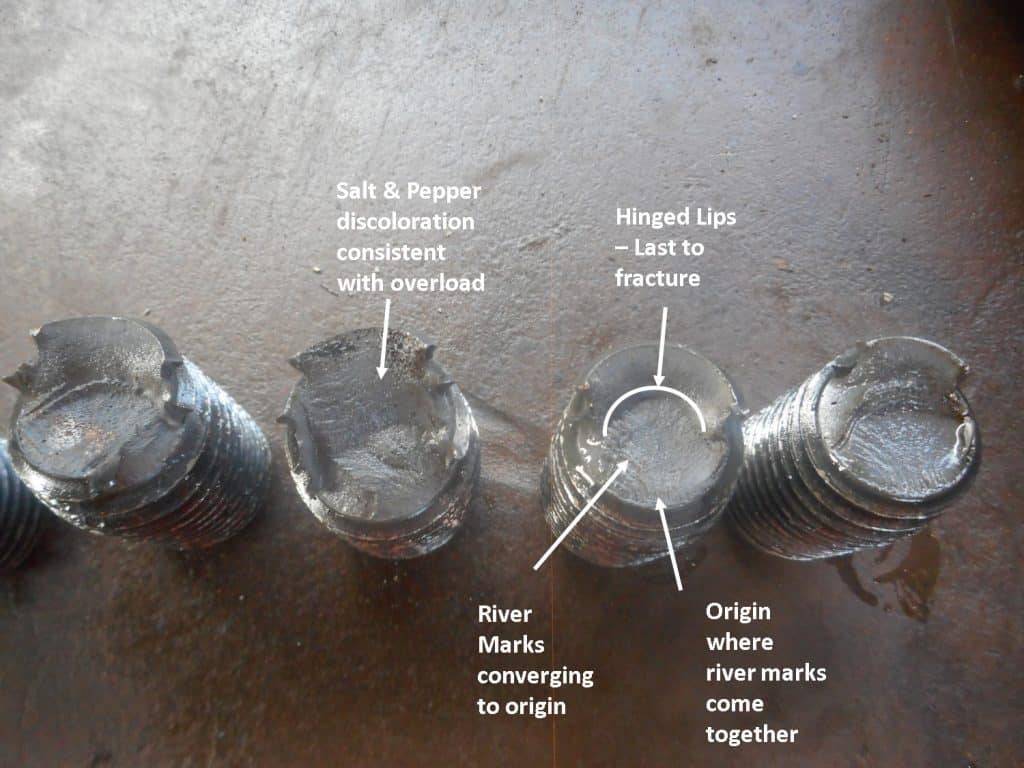

#1 – “With the photo of eight I’d say one or two showed indications of fatigue. In the photo of four, the two on the right look to me to be pretty instantaneous. Whatever it was on got a tremendous shot when the last few failed.”

#2 – “The salt and pepper coloring is consistent with overload. The bolts with the flatest fracture surfaces were the first to go due to a sudden instantaneous overload. The others with the hinged lip where second to go as a result of the first ones failing.

They originated at the bottom where the river marks came together and the fracture origins are consistently at the base of a thread.”

#3 – “Looks like pure overload to me. Whatever it was it seems to be instantaneous – perhaps something locked up.”

I drew this up so I could describe the details they gave me about the fractured surfaces themselves. Keep in mind these are just observations from pictures without context of how the bolts where used, materials, etc. This was a pretty easy pattern to identify, that did not require more technical testing like SEM and/or other lab level testing. For that kind of depth you would need to consult experts like Annelise Zeeman at Materials Life.

I offered a link with more about Overload from our past LI blogs.

Our friend replied to us, regarding our response about his failed parts:

“Hello Robert. First of all, I want your for your time and action in considering my request. Yes, I really enjoyed going through the documents and links you’ve provided- help a lot.

“I see your staff are real experts!. They are not physically seeing the failed bolts and the whole configuration of the hydraulic flange where these bolts are installed, but their analysis is perfect. Their analysis suits what actually happened. With this help, I will finalize my RCA. Thanks for your help as well. Highly appreciated. Kind Regards.”

Originally the submitter suspected fatigue, but after reaching out to experts who could just observe the failed surfaces, he realized that it was overload and not fatigue. This would change the direction of his RCA and its findings.

This is how learning on LinkedIn (LI) is supposed to work my friends! I would like to thank the person who submitted the pics, my metallurgical friends for sharing their expertise and LI for providing the forum for us to share.

Take care!

Update 3.13.18. I wanted to thank all of the veteran materials engineers that have chimed in to offer their inputs about this case. The sharing is what LI is all about (at least to me).

I did want to put this post into proper context though. For those you have followed my posts in the past, you know one of my goals has been to educate first responders about ‘why’ they should save broken parts.

In this case we do not have hi res pics to get into the details, material specs or operating context, but then again we are not doing the RCA ourselves. We are just exploring a hypothesis about ‘how could these bolts have failed?’. There will certainly be a deeper drill down to explore how the fatigue-to-overload patterns came to be. Eventually with evidence the RCA team will collect, they will find decision errors based on system flaws.

Here is another case where we had more context surrounding failed bolts.

Remember, materials engineering is a very complex scientific field. In our experience, about 80% of the time a trained eye can determine the basic call of erosion, corrosion, fatigue and/or overload. However, that does not determine how and why those patterns came to be, that is the role of the investigator in the course of the investigation.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply