For reliability engineers, numbers can be our comfort zone. Predictions, modelling, analysis and results, work that is rigorous, data-driven, and essential for complex systems – but does it always tell the full story?

Recently completing Level 1 of the CIEHF Cross-Sector Learning Pathway has led me to consider system reliability in a different light. Technical performance alone does not guarantee success and to truly understand reliability, we must also account for the human component – the operators, maintainers, and decision-makers whose actions are inseparable from system outcomes.

From Technical Models to Socio-Technical Systems

Traditionally, in my experience at least, Reliability and Maintainability (R&M) focusses on hardware (and sometimes software – although that is a whole other article!), determining system performance through a combination of prediction, calculation and risk reduction through redesign, redundancy or other preventative measures. Extremely valuable work, but ultimately incomplete when it does not consider the human element of the system.

Overall system performance emerges from the interaction between people, technology, and context. An availability model that ignores operator workload or maintainer fatigue may theoretically meet targets yet struggle to deliver in real operations because tasks are simply too complex or too demanding for the people expected to perform them.

The pathway reminded me that systems are not just technical constructs but socio-technical entities, and reliability engineering should attempt to reflect that reality.

Rethinking ‘Human Error’

Human error is often treated as an unpredictable variable, or worse, as a convenient explanation when things go wrong. In reality, human error is rarely random, it typically emerges from the conditions under which people are working, such as unclear procedures, poor ergonomics, excessive workload, or time pressure.

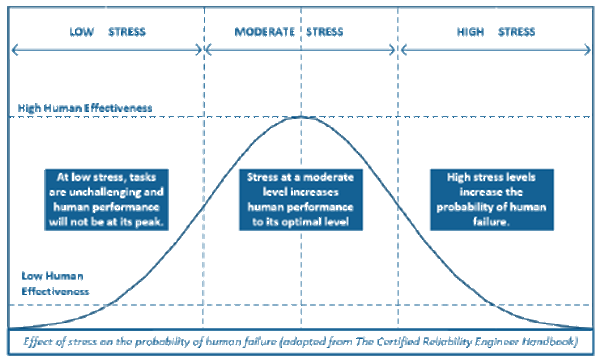

The graph below illustrates this relationship by showing how human performance changes with increasing stress. At low stress levels, boredom leads to reduced performance but as stress rises, engagement increases and performance improves, reaching an optimal zone of efficient functioning. Beyond this peak, additional pressure causes overload, strain, and ultimately burnout, significantly increasing the likelihood of errors. Understanding these Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs) allows us to design systems that support people, rather than blame them when conditions set them up to fail.

In a previous role, I recall a root cause failure investigation identifying an issue where end-users had misinterpreted a procedure. At the time this was simply classified as ‘human error’, but considering the other factors involved (new system, unfamiliar process, time pressures etc.), I now see it was unlikely to have been the individuals at fault, but the environment created around them.

Reframing human error in this way shifts responsibility from individuals to system design. Instead of asking “who made the mistake?” we should ask “what conditions made the mistake likely, and how can we design them out?”

Taking a Broader View

I have seen Design for Support (DfS) activities deliver significant benefits in terms of maintainability – “Can a maintainer easily access and remove/replace the equipment?” “Can the equipment be removed from its location safely within manual handling limits and without the need for additional lifting arrangements?” These are important questions and valuable work, but they represent only part of the picture.

Ergonomics extends far beyond dimensional fit. It is about inclusivity, adaptability and recognising that people bring diverse physical, cognitive and perceptual capabilities to their work. By designing systems that accommodate these qualities, we create environments that foster efficiency, resilience, and job satisfaction.

Taking this broader view means that well-designed systems are not only safer to operate and maintain, but also more dependable, sustainable, and human-centred in the long run.

Integrating Human Reliability with ‘Traditional’ R&M

The key learning point for me is that Human Factors and R&M are not competing disciplines, they are complementary. By embedding practical Human Reliability principles into R&M analysis, we gain models that better reflect how systems are actually operated and maintained.

Traditional methods such as Reliability Block Diagrams (RBDs), Failure Mode, Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA), Fault Tree Analysis (FTA), Reliability-Centred Maintenance (RCM), Maintenance Task Analysis (MTA), and feedback/reporting systems like FRACAS or Root Cause Analysis (RCA) remain essential. But these methods become far more representative and relevant when informed by human reliability assessments, workload analysis, and a deeper understanding of the physical and cognitive demands placed on people.

Integrating human reliability into these established techniques doesn’t require reinventing the wheel. It can begin by extending the familiar:

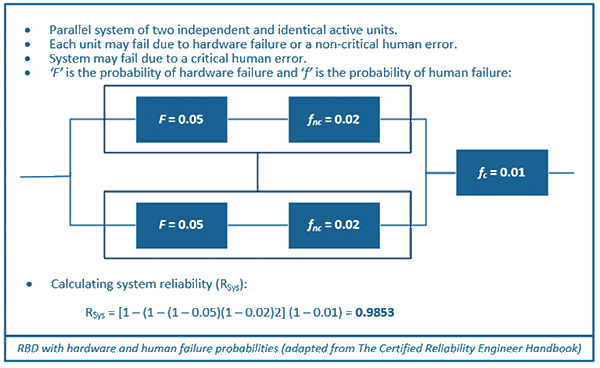

- Incorporate human error probabilities for critical tasks into RBDs and R&M modelling (see example below).

- Consider human failure modes (misinterpretation, omission, wrong action) alongside hardware/software failure modes in FMECA.

- Represent human actions/inactions as basic events with probabilities in FTA.

- Assess task error likelihood and workload when performing Preventive/ Corrective Maintenance (PM/CM) tasks in RCM.

- Highlight workload spikes, decision points and fatigue risk in MTA.

- Classify and trend human contributions in FRACAS/RCA beyond vague attributions like ‘operator error.’

Systems designed this way will not only be more technically robust but also practical, sustainable, and user-friendly.

For more complex or safety-critical systems, advanced Human Reliability Analysis (HRA) techniques such as Technique for Human Error-Rate Prediction (THERP), Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique (HEART), or Systematic Human Error Reduction and Prediction approach (SHERPA) may be more appropriate, allowing more formal modelling of task error likelihood and performance influencing factors – more to follow on these in a future article as I continue my learning journey…

A Shift in Mindset

Human reliability is often considered as a residual factor, something to acknowledge but not quantify or integrate. The pathway has forced me to confront that assumption and I now see human performance not as a source of variability to be managed, but as a core determinant of system reliability.

The conditions in which people work and the effect on performance are fundamental to R&M and this shift in mindset is one that I intend to carry forward in my practice.

Alignment with International Standards

The recently published IEC 62508:2025 – Guidance on Human Aspects of Dependability makes it clear – system dependability is not determined solely by components and technical design, but also by the performance of individuals, teams, organisations, and their interfaces. It emphasises the need for structured approaches to assess and enhance human reliability throughout the system lifecycle.

This guidance reinforces a critical point: human reliability is not a peripheral concern – it is fundamental to the discipline of dependability. As engineers, consultants, and technical leaders, we have both the capability and the obligation to embed human reliability more deliberately into our engineering and support practices.

Closing Reflection

Engineering and R&M in particular, is often thought of as a numbers game, but behind those numbers are people, operators, maintainers, and end-users, whose performance defines whether a system succeeds or fails in the real world.

As I continue my work, I am committed to embedding human reliability at the centre of system design and analysis. Because ultimately, reliability is not just about the technology we build, it is about how people and technology perform together in context.

I would be interested to hear from others in reliability, maintainability and support engineering across defence and related sectors:

How are you integrating human reliability into your own work, and what challenges have you faced in doing so?

… and for those working in Human Factors:How do you integrate your work with reliability, maintainability and support engineering and what are your tips for successful collaboration?

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply