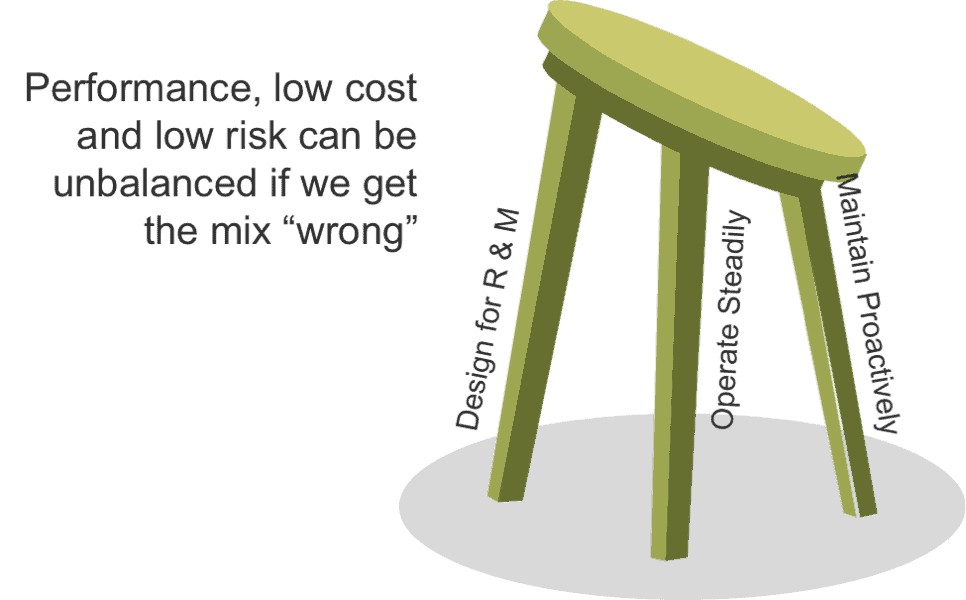

Our simple 3 legged stool model from part 1 will deliver high performance at low cost and risk – i.e.: high productivity. It is important however to keep the legs intact! Doing so requires a bit of investment. In thermodynamic terms we need to put some energy into the system to keep the entropy from growing. That energy is investment in maintenance and the payoff comes in the form of steady, predictable revenues with a high margin for profit. Those words should be music to accountants’ ears.

It’s important that they also recognize that the focus on costs, reduces the energy you put into the system and allows the entropy (chaos) to increase. That mistake, failing to invest enough will destabilize the stool.

Keep in mind that each leg of the stool requires some amount of spending (energy) to avoid entropy creep (destabilizing chaos). You want it balanced, not too much, not too little, just the right amount to keep the top of the stool level.

Design:

Once design is established we can do little to change it without a lot of investment. Better to spend a bit more up front than a lot later. Whatever design we end up with will be subjected to the natural forces of nature, entropy will increase relentlessly and checked only by the energy we put into good operational practices and maintenance.

We need to invest in design that produces a system that is reliable and easy to maintain quickly. It’s no secret that reliable products are often more expensive than unreliable ones. We can expect our capital spending on the system to be a little bit higher than if we buy the cheapest, or design the cheapest that we can.

Be wary of the tendency of entropy to creep into just about everything, including our thinking!

New systems are not built without good business cases. Usually we want our business case to be well above some minimum acceptable financial “hurdle rate of return” so that it gets chosen from among competing projects. That creates an opportunity for entropy to creep into the process of developing business cases! Here’s how. The project is someone’s proverbial “baby”. They want it. They will do just about anything to ensure its viability. So, to ensure the project gets built, they embellish the business case. They show that the idea (new project) has the highest possible return on investment. That gets done by minimizing initial cash outlay, downplaying both the risks and costs and optimistically forecasting revenue potential.

All of those are best-case scenarios. More often than not, here’s what happens to those. Projects often come in late and over budget. That’s entropy growth from project risks that don’t play out as you’d wish. Lowball estimates of costs and schedule get the project into trouble. Those were risky decisions, in part because they are overly optimistic.

That early lowball estimate also most likely didn’t allow for a bit of engineering to ensure high reliability and maintainability. That will be a problem later once operations begin.

Operations:

Ensuring trouble-free operations means having a design that is operable and a crew of operators that knows what it is doing. Operability is another design feature – enough said.

One byproduct of projects that are late and over budget is poor training or even no training. Training is usually timed to occur late in the project, near startup and operations when it is needed. However, if the project is over-budget, then the training part of the budget is an easy target. Sadly, that is one target that is often too easy to hit, so training suffers. Decisions to pullback on training (reduce your energy input) will increase entropy and chaos. Your operators will struggle to run the system as it is intended and will make mistakes. Many of those mistakes will result in equipment failures.

Put energy into keeping entropy at bay through training. Operators can help keep the system in good condition by doing some very basic things to take care of it, be diligent observers of how well the system is operating and spot problems early.

Maintenance:

Getting the maintenance right can be more complex than the other two. I’ll discuss that in the third part of this series but suffice to say here that a small amount of energy (i.e.: spending) can pay off (I.e.: reduce entropy) with a huge payback.

Economics:

Assuming we get the right amount of energy (spending) applied to get a balanced length of each leg we should have minimal entropy growth over time. So far the focus has been on under-spending. In fact, it is also possible to spend too much – effectively making a leg of the stool too long relative to the others.

Too much design focus is tantamount to striving for perfection. You may never achieve it but you can spend a lot of money trying. Even if you do achieve it, maintaining it might be a challenge. You won’t be able to engineer-out all of the possible failures and all the possible factors that could lead to human error. Over-engineered systems can be hard to operate unless the engineering effort goes into operability. What we want to achieve is balance – not perfection.

Likewise, you can spend too much on operations training taking the level of knowledge well beyond that needed for safe and effective operations. And in maintenance, you can spend way too much. Some people consider that maintenance occurs somewhere along a spectrum from reactive to completely proactive. That’s an inaccurate perception – the best maintenance programs will include preventive, predictive, detective tasks and allow some failures to occur. Not all failures are worth being proactive about.

Getting that balance is what we want to achieve and that requires careful thought, analysis and decision making.

In part 3, I will focus on Entropy and Maintenance.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply