Reliability Engineering has a bias that is both practical and measurable: simpler systems tend to be more reliable. This is not a philosophical preference for elegance; it is an outcome rooted in how failures occur, how they propagate through architectures, and how uncertainty accumulates when complexity grows. When we say “simple,” we do not mean “unsophisticated.” We mean fewer parts, fewer interfaces, fewer operating modes, fewer dependencies, and fewer opportunities for human and environmental variability to turn into functional failures.

Assessing complexity outcomes through Reliability Block Diagrams

A useful starting point to asses an operating system, is the classic Reliability Block Diagram (RBD). By definition, a system is a collection of items whose coordinated operation leads to the proper functioning of the system itself. The collection of items includes subsystems, components, software, human operations, etc. In RBDs, it is crucial to account for relationships between items to determine the reliability, availability and maintainability of the overall system.

Series Systems

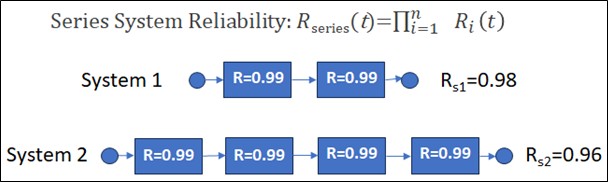

In a series system every block must function for the system to function. The system reliability is the product of the block reliabilities as shown in the equation and example below.

The mathematics is uncompromising. Even though the reliability of subcomponents is high (at 0.99), the more subsystems we have in series, the lower the system reliability (RS1>RS2). In other words, as the number of required in-series elements increases, system reliability decreases even if each element is individually “good.”

Parallel Systems

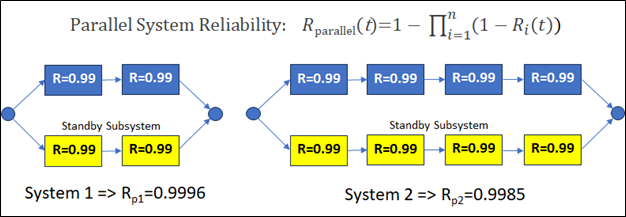

In parallel systems, we introduce the concept of redundancy. We add redundancy in order to limit the advent of system failures. If one subsystem fails, then other standby subsystems can be activated and keep the overall system running. This is illustrated in Diagram 2 below.

However, adding redundancy is costly. The trade off is higher reliability but the economics have to be carefully evaluated. In terms of simplicity again, one can note that even in the parallel system, the less there are components, the higher the system reliability (i.e. Rp1>Rp2).

Parallel redundancy can dramatically improve reliability if implemented correctly. Condition monitoring can reduce functional failures by enabling proactive interventions. However, these additions must be justified by net economical benefit.

Failures Induced through Complexity

Complexity often adds series elements: sensors, connectors, software checks, actuators, valves, power supplies, communication links, and configuration states. Each new element introduces a new way to fail and a new requirement that must be satisfied to deliver the required function.

Complexity also increases the number of interfaces, and interfaces are where reliability quietly erodes. Many field failures are not due to the “main” component failing, but due to connectors, seals, wiring terminations, solder joints, misalignment, loose fasteners, calibration drift, and contamination paths—essentially, boundary conditions. In probabilistic terms, interfaces multiply the opportunities for variation. In physical terms, they create discontinuities where energy, fluids, signals, or forces transition from one domain to another. Simpler systems, with fewer interfaces, present fewer “weak” links.

FMEAs and complexity

Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) reinforces the effects of complexity. A simple design typically has fewer credible failure modes, fewer causal chains, and fewer “unknown unknowns.” As designs become more complex, the failure-mode space grows faster than linearly because interactions between components create emergent behaviors. A valve plus a controller plus a sensor is not merely three items; it is a coupled loop with dynamic stability, timing, noise, drift, and configuration dependencies. That coupling expands the set of ways performance can degrade into failure, and it increases diagnostic ambiguity—making it harder to detect problems early or isolate root causes quickly.

Maintainability and other Operational Factors

Maintainability and human factors are equally relevant. Reliability is not only about intrinsic component life; it is also about how the system is operated, maintained, and restored. Complexity increases the probability of human error during installation, troubleshooting, calibration, and repair. Especially under time pressure and imperfect documentation. In many operational environments, “maintenance-induced failures” are a meaningful contributors to downtime. A simpler system often reduces maintenance touchpoints, makes incorrect assembly harder, and improves error detectability. In reliability terms, it reduces both the likelihood of failure and the uncertainty in restoration time, improving availability as well as reliability.

Do “simple” systems mean “better” systems?

None of this suggests that “simple” automatically means “best” or “safer”. Engineering frequently demands added complexity to manage risk: redundancy, monitoring, protective functions, or fail-safe architectures.

For example, airplanes use multiple redundant systems because Reliability Engineering assumes parts will fail, and the consequences of failure in flight are very high. So critical functions—like hydraulics, electrical power, sensors, and flight controls—are built with backup paths in parallel and kept as independent as possible. This way, one failure does not cause loss of the whole function, and the aircraft can keep operating safely until it lands. Redundancy and subsequently complexity also improves availability by reducing flight delays and cancellations caused by single-component faults.

Regulations leading to more Complex Systems – the Carburetor example

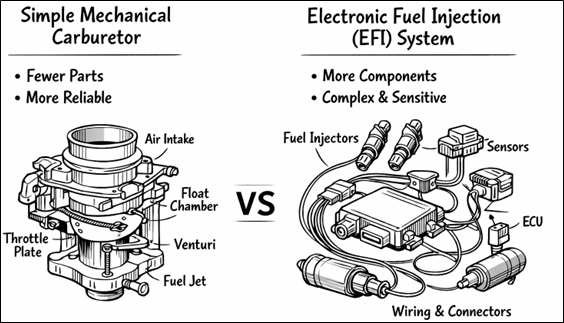

Regulatory requirements often lead to the need of more complex systems at the expense of Reliability.

Even though a mechanical carburetor tends to be more reliable in the classic reliability-engineering sense (fewer parts, fewer interfaces, fewer failure modes, and generally easier fault isolation and repair – See Diagram 3), modern fuel and emissions regulations effectively forced the industry toward Electronic Fuel Injection (EFI). The reason is that emissions compliance is fundamentally a control problem. In that regulators require tight, repeatable control of air–fuel ratio across cold starts, altitude changes, transient throttle events, component aging, and a wide range of ambient conditions. The performance a purely mechanical metering device struggles to deliver consistently. EFI achieves this by adding sensors, an ECU (Electronic Control Unit), and actuators (injectors) to measure key variables and continuously correct fueling in closed loop, enabling catalytic converters to operate in their narrow “sweet spot” and keeping pollutants within mandated limits. In practice, this is a deliberate trade: we accept increased system complexity and a larger electronic/connector failure surface in exchange for the precise control needed to meet emissions targets, fuel economy requirements, and on-board diagnostics expectations.

Conclusion

A practical way to frame the principle is this: reliability is harmed by the accumulation of failure opportunities and uncertainty. Simplicity reduces both. It trims the number of required functions, the number of interfaces, the number of states, and the number of maintenance touchpoints. It narrows the FMEA, improves diagnostic clarity, accelerates reliability growth, and reduces maintenance-induced risk. In an RBD sense, it removes unnecessary series elements. In a life-cycle sense, it reduces the cost and time required to understand and control failure behavior. The most reliable systems are rarely those with the most features; they are the ones with the fewest ways to fail while still meeting requirements. Reliability Engineering, at its core, is the disciplined pursuit of that outcome.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Ask a question or send along a comment.

Please login to view and use the contact form.

Leave a Reply